The hill of Udaigiri (also spelled Udayagiri, Udaygiri, etc.) is located in the Vidisha district of Madhya Pradesh. It stretches about 2.5 km from the northeast to the southwest reaching its highest altitude of 350 feet at the northeast end. A great depression in the middle of the hill divides it into two parts. This depression is in the form of a passage running east to west across the hill. The northwest boundary of the hill is marked by the Halali River (also known as Bes River) while the Betwa River flows in the east of the hill, a little distance away. The hill is located about 6 km away from the town of Vidisha. The region in and around Vidisha was known as Dasharna (दशार्ण) and referred to in Buddhist literature as well as in the works of Kautilya.1 Mesolithic tools and upper paleolithic tools discovered on the hill indicate an early occupation at the site.2 The historical antiquities at the hill were first reported by Alexander Cunningham in 1880. He tells the hill had been extensively quarried in the past for its white sandstone resulting in the serious loss of valuable antiquities.3 As Cunningham had assessed that Besnagar would have been a famous Buddhist city in the past, therefore H H Lake, at the behest of the then Maharaja Scindia of Gwalior, took up a six-week exploration exercise at Besnagar and Uadaigiri in 1910 in order to discover Buddhist antiquities of the town.4 1913 witnessed the formation of an Archaeological Department in the state of Gwalior and D R Bhandarkar was given the task of further excavations at the site. About the earlier work done by Lake, Bhandarkar writes, “Most of the mounds dug by Lake were proved barren, and the excavations of the rest, though it was not quite as thorough and scientific as was desirable, at any rate conclusively showed that they did not contain remains of a period earlier than the Gupta.”5 Bhandarkar conducted two seasons of excavations, one in 1913 and another in 1914.6 Though the reports from Lake and Bhandarkar do not speak about the excavation carried out by them on the northern top of the Udaigiri hill, Dass tells Lake also dug a trench across the plinth of the Gupta temple on the northern hilltop at Udaigiri.7 She also mentions Bhandarkar took up excavation in 1914 on the top of the northern hill at Udaigiri and as his reports do not provide any details and description of findings, also his field diaries are not traceable, therefore it would not be improper to say that Bhandarkar left the site in utter confusion.8

The excavation carried out by Bhandarkar was the only excavation at the site as no further attempts were ever tried till now. The site did not garner much attention after 1914 till K P Jayaswal takes up the study of Chandragupta II and his predecessors in 1932. In his study, he takes into account the two large panels at Udaigiri, the Varaha panel, and the Anantasayana panel. Jayaswal opines the devotee carved in both panels is a portrait sculpture of King Chandragupta II and thus these panels reflect a political allegory.9 A monologue on Udaigiri was later written by D R Patil in 1949.10 By this time, the Gwalior Archaeological Department had carried out some necessary conservation works and numbered the caves in a proper sequence. The numbering given by Cunningham to a total of ten caves had now increased to twenty with the findings of new caves and cells on further exploration. The monologue from Patil collected all the scattered information into a single place and provided up-to-date information on the caves and sculptures. While we had to wait till the early decades of the twenty-first century for a comprehensive attempt in studying the site in its political, geographical, and cultural context, the sculptures at Udaigiri were included in various studies on the Gupta art and architecture. The first scholar taking up the iconographic study was V S Agrawala however he did not take all the sculptures into account and kept his focus primarily on the Varaha panel.11 He mentions that the sculpture doubtless represents for the first time the vigor of which Gupta art was capable. He also emphasizes the theme of the descent of Ganga and Yamuna and both being merged together flowing into the ocean. Taking a political meaning of this theme, Agrawala writes, “The rivers Ganga and Yamuna, the two arteries of Madhyadesa, seem to have been adopted as the visible symbols par excellence of the homeland of the rising powers of the Guptas in the reign of Chandragupta II Vikramaditya.”12 Debala Mitra also takes up the Varaha panel in her iconographic study of the cave. She successfully interpreted various figures of the panel and mentions the figure behind the naga may be the portrait sculpture of the donor without giving any explicit identification.13

The next scholar who worked on iconography was J C Harle. He described various imagery at the site including mukhalingas, Vishnu images, the Varaha panel, Mahishasuramardini, and a few others. Without giving reference to Jayaswal, Harle also suggests a possibility that the devotee carved behind the naga in the Varaha Panel may be Chandragupta II.14 Joanna Williams includes all the significant sculptures at Udaigiri in her magnum opus on Gupta art. For the Varaha panel, she tells the closest literary source appears to the Matsya Purana where Vishnu is invoked with reference to the twelve Adityas as islands, eleven Rudras as towns, eight Vasus as mountains, siddhas as billows, birds as winds, daityas as crocodiles, rakshashas as fishes, and Brahma as great patience, etc.15 She followed Mitra in the identification of various figures over the Varaha panel except the figure behind Shesha whom she identified as Samudra and Agrawala for the Ananatasayana panel. Williams’ focus was to arrange the Gupta monuments and remains in chronological order, and taking note of two inscriptions at Udaigiri, one from the reign of Chandragupta II and another from Kumaragupta, she assigns the various caves to these two periods.

Two important studies came out in 2001, one was from Michael Willis16 who publishes later-Gupta period inscriptions at Udaigiri with an assessment of how the site was in use after the departure of the Guptas from the scene and the second was a Ph.D. thesis from Meera Dass17 who took up a comprehensive study of the site in the context of its political, cultural, and historical relationships with the nearby sites of Sanchi, Besnagar, and others. In his study, Willis also takes up the case of the Bija Mandal and its inscription that mentions Udaigiri. Willis suggests a Sun temple was established sometime on the top of the Udaigiri hill and the temple gained significant prominence during the eleventh-twelfth century CE to the extent that the Muslim rulers of Delhi had to demolish it twice, first in 1234 and again in 1292. Dass proposes various possibilities such as the site might be in use as an astronomical observatory, rainwater harvested in tanks on top of the hill, and water let out to flow down the hill creating a visual treat of images emerging out of an ocean, the hill was the place where the famous iron pillar now in the Qutb complex was originally installed, etc. Some of her theories are convincing while a few may need some more research to draw a conclusion. In 2009, Willis takes one more attempt to define the ritual meaning of the icons and sculptures at the site.18 His main proposition was the role of water and astrology in the context of the visual impact of the panels. He asserts that astronomy plays a major role, and the placement of the Varaha panel, Narasimha image, and the Anantasayana panel represented the start of the kalpa when the earth was taken out of an ocean, the dawn or the mid-point of the kalpa and the eternal sleep of Vishnu as the end of the kalpa respectively. These are some of the important past studies about the hill and its remains, there would be many more studies in addition to the ones enumerated above, however, those are out of scope for this article.

As mentioned above, the discovery of Mesolithic and upper Paleolithic tools on the hill proves an early occupation. Though there is no direct Maurya connection to the hill, however, as Ashoka stopped at Vidisha during his trip to Ujjain, it is probable that he would have also visited this hill or passed through it. Who were the occupants and how they used the hill during the pre-Mauryan period is not certain, however, natural rock shelters, as many as twenty, with paintings and remains of Shankha-lipi inscriptions discovered on the northern and southern sides of the north hill also indicate that the hill was used for ritualistic purposes. Though the dating of these paintings is a complex topic, Dass assigns these shelters to the post-Mauryan period.19 The site was in use before the Guptas also evidenced by excavations overlapping on the Shankha-lipi inscriptions. Dass and Willis have discussed this point in detail in their studies. During the Guptas, the hill was taken up for significant art activities, and various caves, sculptures, and temples were attempted. What happens to the hill and its shrines after the Guptas is not very evident, however, the hill was in use till the eleventh-twelfth century as modifications were made in its shrines over the northern part of the hill. The first epigraphical reference to Udaigiri appears in an eleventh-century inscription found at Vidisha.20 As the inscription also speaks about a Sun temple, it is suggested that the temple stood on the top of the hill. The presence of eleventh-century inscriptions in Cave No 19 also suggests the hill was very much in use till that time. However, very soon it might have lost its sheen and the nearby towns of Besnagar and Bhilsa would have taken over its religious and cultural role.

Monuments – The hill has a total of twenty different cave shrines excavated on its northern and southern parts, most of these lying over the southern part. Cunningham enumerated a total of ten caves, however, the number was increased after the exploration by the then Archaeological Department of the Gwalior state.

Cave No 1 (Suraj Gufa) – This cave is located on the southernmost part of the hill and is the only excavation on this part of the hill. It faces east and is partly man-made and partly rock-cut. A ledge on the hill was converted into a chamber by constructing one of its lateral sides using dressed stone and covering the front with a mandapa (portico). The inner chamber measures 7 feet by 6 feet and the front mandapa is 7 feet square.21 Four front pillars support the mandapa. The intercolumniation gap between the two middle pillars is 3 feet and the gap between the middle and the side pillars is 1 foot, a typical Gupta period characteristic. The pillars are simple in design, their base is square carrying a shaft that first is octagonal and then turns to sixteen-sided near the top. The capital is carved with the vase-and-foliage motif. Williams assigns this cave to the end of Chandragupta II’s reign and considers the front pillars to provide an important step in the development of the capital. The vase-and-foliage (purna-ghata) or overflowing vase motif is the first instance of such design in the Gupta repertoire. She hesitates to define the origins of this capital motif to Mathura but advances that its origins to be found somewhere in the Malwa region.22

The main image inside the chamber was hewn out of the rock however, it has been chiseled off leaving traces of its outline. A standing image of Parshvanatha has been placed inside the chamber. This image was not there during the visit of Cunningham and Patil, Dass tells it was placed sometime in the 1950s.23 A yearly ritual followed by the local community makes offerings to the Sun god in this cave, taking into account that the image chiseled off was of the Sun god and thus its local name Suraj Gufa.24

Cave No 3 (Kumara Cave) – This cave was not included in Cunningham’s account. The entrance is through a rock-cut door that has well-cut jambs but is devoid of any decoration. The cell measures 8 feet by 6 feet 2 inches.25 On the rear wall is carved an image of Kartikeya. The god is shown with two arms, his left arm is resting over his waist while in his right arm, he holds his shakti (spear). and has three strands of hair thus representing this trisikhin character. Harle considers the head of the image as one of the best-preserved faces of any of the Udaigiri sculptures. Harley sees a great influence of the Mathura art of the Kushana period over the Gupta period sculptures and applying the same thought process over this image, he writes, “The powerful chest can best be seen in the Kartikeya image. The lower legs, feet slightly apart, knees bent almost backward, also recall the typical Mathura stance; on the other hand, the tight cylinder of the thighs tapering to the relatively slender waist, recalls the Nagarajas of Sanchi and the Narasimha in Gwalior and seem to be typical of eastern Malwa.”26

Cave No 4 (Vina Cave) – This cave was numbered third in Cunningham’s account and named Vina Cave because an image of a male musician playing a vina was carved over the doorway.27 The inner chamber is about 14 feet long and 12 feet broad. The entrance doorway is 6 feet high and about 3 feet wide. Two pilasters carved next to the entrance suggest the cave once supported a mandapa in the front. Between these pilasters and the doorway are cut two dvarapalas. The doorway contains four shakhas (bands), all decorated with different floral and foliage designs. The second and fourth shakha (band) forms the typical T-shaped design of the Gupta style where the lintel extends beyond its uprights. Five circular bosses alternating with chaitya arches are carved over the lintel section of the second shakha. A man playing a vina (lute) is carved on the leftmost boss, the next boss has an image of makara and the next has a lion’s face. The image inside the fourth boss is very much damaged and Cunningham, taking symmetry into account, suggests that it might contain the image of a makara as that of the second boss. The image inside the last boss is much damaged but the outlines suggest it is of a musician playing some instrument, Cunningham mentions the instrument as sarangi.28

The mukhalinga inside the chamber is considered one of the best specimens of the Gupta period. The face is very charming and if there was no third eye then its identification with Shiva would have been very tough as the face does not show any typical characteristics of him. The face is round and bears a smile over the ends of the thick lips. The eyes are half-closed and have high-arched eyebrows. The hair is tied in a knot and its strands out of the knot fall on the sides of the face. Dass opines the seven hair strands coming out of Shiva’s hair-knot are the seven streams of Ganga when the latter started flowing out of Shiva’s hair locks.29 Williams dates this cave to the period of the successors of Chandragupta II, stating 413 CE was taken as a dividing point and this cave falls just after this dividing point. The reason for this she explains is the more three-dimensional and projected figures of the dvarapalas, simplified but refined doorframe, and projected pilasters.30

At a right angle to this cave is an open cell, measuring about 11 feet in length and about 7 feet in width. A few figures are carved at the rear and lateral walls of this cell. There is confusion regarding the number of the figures. Harper tells a total of nine figures are carved with Kartikeya on the left lateral wall followed by sapta-matrkas over the rear wall and a badly mutilated image on the right lateral wall. Identification of Kartikeya was done on the basis of a barely perceptible outline of a cock over a standard as explained by Harper. She also says the presence of Kartikeya as the head of the group and the absence of Shiva in this role is notable, however, she suggests that the figure on the right lateral wall may be identified with Shiva or a guardian.31 Dass counts a total of eight figures, one each over the lateral walls and six on the rear wall. She identifies the figure on the left lateral wall as that of Virabhadra instead of Kartikeya as taken by Harper. The six figures on the rear wall represent the six of the sapta-matrka group.32 She is right in counting the figures on the rear wall as there are six figures but not seven as mentioned by early scholars. All the figures are badly damaged and from what remains it appears that the matrkas were carrying a child, either on their lap or placed near their feet. Their weapon emblems were carved over their head, trishula of Maheshwari is still visible on the second figure from the left. There are remains of some circular object over the head of the first figure, and it may be a lotus, the emblem of Brahmani, the first matrka.

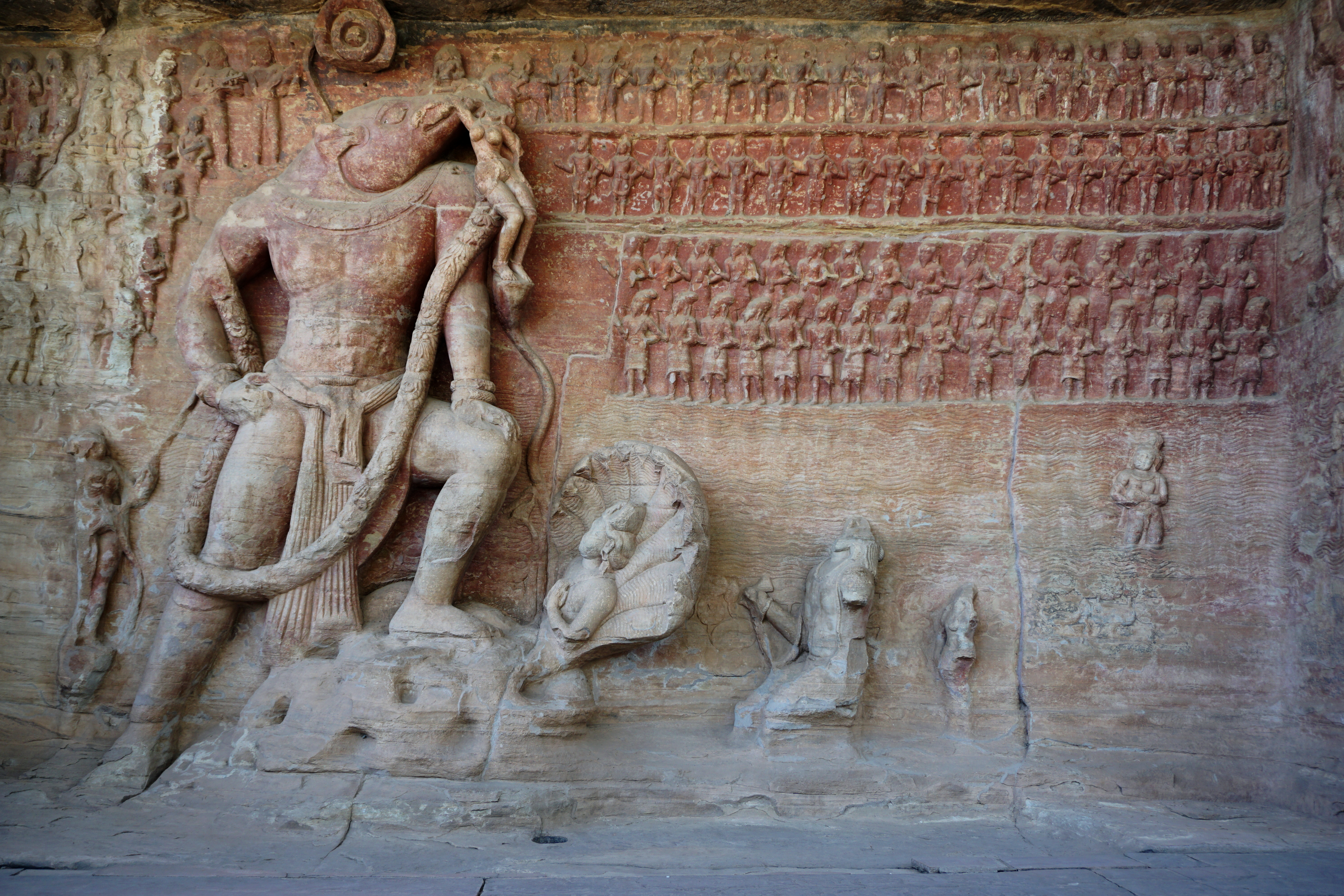

Cave No 5 (God’s Valley) – This cave is numbered four in Cunningham’s account. He gives its measurements as 22 feet in length, about 13 feet in height, and 3.5 feet in depth.33 The present name, God’s Valley, of the cave is probably due to the number of images carved over this panel, appearing that the whole of heaven has come down to witness some monumental moment. This panel is amongst the largest ones in India, only second to the Arjun’a Penance at Mahabalipuram. The theme is a well-known mythological sequence where Vishnu takes the form of a varaha (boar) to take the submerged earth, carrying it over his tusks, out of an ocean. Williams takes this sculpture as one of those works of art in which a theme is represented without major precedents and in which the sculptor seems to have drawn more upon the realm of ideas than of visual forms.34 The Varaha takes center stage where he is shown standing in alidha-mudra with his right foot firmly placed over the ocean and the left foot kept over the coils of Sheshanaga, the latter is depicted with hands in anjali-mudra (folded) and a hood made of thirteen heads, seven in the front and six behind in the intervals. In the background are carved a multitude of figures representing various deities and sages. Debala Mitra has successfully identified many of these figures in her erudite article.35 Starting with the top row, on the immediate right of Varaha are two musicians, one playing guitar and another a vina. They may be Narada and Tumburu. Beyond them are seven rishis, Saptarishis. Below them are the four rows of figures, all more or less the same, representing the seven classes of rishis.

The first row of figures on Varaha’s left has twenty-two figures. The first figure is that of Brahma shown immediately above the head of Varaha. The next figure is of Shiva shown seated on a bull. The rest twenty figures are identical in their dress and ornaments. They all stand with slight flexion. The first twelve have a halo behind them but the heads of the eight are damaged. The first among these twelve has a vajra in his left hand and thus may be Indra. The next figure has a pasa (noose) and thus may be Varuna. Mitra takes these twelve figures including that if Indra and Varuna to represent dvadash-Adityas. The rest eight may be taken as Ashta-Vasus. The first figure among the Vasus is Agni as he is depicted with a flaming head. The next figure is Vayu depicted with inflated hair and a banner in his left hand. The second row has twenty figures in total. The first eleven are different from the rest nine by the mode of wearing a scarf and ithyphallic feature, the third eye, and thus should represent ekadasha-Rudras. In the bottom two rows have thirty-two rishis. Willis takes the Varaha figure as the representation of Vishnu being stirred from his sleep at the end of the monsoon claiming the orientation of Varaha towards the east enables the light of the rising sun throughout the dakshinayana including the waking day of Vishnu in the month of Karttika.

There are two kneeling figures shown behind Sheshanaga. Cunningham suggests that the larger figure may be of the ocean king.36 K P Jayaswal was the first scholar who brought to attention the political allegory of the image after considering the references from the play Devi-Chandragupta, which compares the rescue of Dhruvaswamini by Chandragupta II from the hands of enemies to Vishnu’s delivery of the Earth from the ocean. Jayaswal tells when he saw the Varaha panel at Udaigiri with its subsidiary statues of goddesses on the Gupta coins, the whole architectural scheme gleamed onto him. He found himself face to face with the standing figure of Varaha, in the pose of Chandragupta II on his coins, rescuing a most beautiful woman by the end of his tusk, receiving the homage of orthodoxy in the persons of rishis and of the crowd playing music. As Vishnu killed Hiranyaksha by assuming the guise of a boar, Chandragupta II killed the mleccha (shaka) by assuming a guise of a woman.37 Harle, without quoting Jayawal, also puts forward the same suggestion that this kneeling figure may be Chandragupta II.38 Williams, who was aware of this suggestion from Jayaswal as well as Harle, does not provide details on the identification of the figure. Meera Dass prefers to go with the identification of the larger figure with Chandragupta II and the smaller figure behind him as Saba Virasena, the latter was the minister of the king mentioned in the inscription in Cave 7.39 Taking a cue from an inscription found in the adjacent Cave 6, Willis explains that the most crucial phrase in that description is “Srichandraguptapadanudhyata”, meaning “meditating on the feet of Sri Chandragupta”. He claims if we accept the parallel between the king and Varaha, then the inscription tells the figure kneeling in front is the Sanakanika prince. He concludes that this provides a fitting hierarchy: the prince who made Cave 6 and installed its image also commissioned the Varaha panel showing his monarch in the Vaisnava guise; in that panel, the Sanakanika depicted himself as the respectful donor. Willis moves ahead with multiple interpretations and identifications. He draws a parallel between Samudragupta and Vishnu claiming Vishnudasa, a feudatory king under Samudragupta, was named so as he was meditating at the feet of Vishnu, i.e. Samudragupta. Thus, the Varaha represents Samudragupta, and the kneeling figure is Vishnudasa.40 There are multiple problems with his theories. The first is that the Sanakanika inscription he refers to is engraved in another cave, though adjacent, but not in the cave where the Varaha panel is carved thus drawing a correlation would be not just. The other problem is drawing a parallel between Samudragupta with Vishnu as there exists none, and if we agree with him then all the kings of all the periods in India could be easily compared with different gods as all were devout religious figures meditating at the feet of one god or other.

On both the lateral sides of the panel, a single theme of the descent of the rivers and their merging into the ocean is depicted. The two river goddesses, Ganga and Yamuna, are shown standing over their respective vahanas, makara, and kachchhapa. This is the earliest instance when we find the river goddesses over their respective vahanas.41 It is also suggested that as Ganga and Yamuna are the two main rivers of northern India, the mainland of the Gupta empire, their figural depiction and final merging with the ocean, represent the dominion of the Guptas over the northern geography of India. In the background, the wavy lines carved in vertical direction, represent their descent from the heavens. In the middle of the panel, the wavy lines become horizontal representing the ocean over the earth. In the ocean is shown a male figure, submerged to his knees in water, carrying a vessel. He probably represents Varuna, the lord of oceans or water. Some scholars have also identified him as Samudra, the lord of oceans. The vessel in his hand probably suggests that he has cordially appeared above the ocean to collect both the river goddesses. He is carved in three places, one each on the lateral sides and one in the background wall behind the kneeling figures. In praise of the theme, Harle writes, “Here at Udayagiri, a unique attempt has been made, moreover, to extend and amplify the scene and give literal expression to more of the accompanying myth and symbolism…..ambitious water imagery is attempted, with incised wavy lines representing water, rows of lotuses, and amongst the water a solitary male figure, probably the personification of Ocean, a minor mythical figure.”42

There was once a large tank in front of the panel separated by a narrow road. Scholars who have suggested water playing an important role in the iconography of the panel, have opined that the water flowing from the tank above the hill was collected into that tank, giving a visual impression of Varaha emerging from an ocean. The tank full of lotuses and other flowers, probably also having fishes and other aquatic creatures, gives a fitting symbolism of an ocean in the overall iconography of the panel. Water erosion marks found at the bottom of the panel are indications that the panel would have been in the water for a considerable period.

Cave No 6 (Sankanika Cave) – This cave is numbered five in Cunningham’s account. The present name is because of an inscription referring to a ruler from the Sanakanika tribe. The chamber is 14 feet deep and 2.5 feet broad.43 The portico in the front is about 14 feet long and 6 feet deep. Five sculptural panels have been carved on either side of the entrance doorway, two on the left and three on the right. The doorway has four shakhas (bands) carved with projected and recessed sections in alternation. The innermost shakha is decorated with a long continuous foliage design. The next shakha has a twisted garland decoration. The next shakha has a triangular teeth design. The outermost shakha is in the form of a pilaster rising above the dvarapalas placed at the jamb base. The pilaster is topped with a bell capital carrying a square member carved with a plant from which emerges two rampant animals, probably lions. While the lintels of all the shakhas are projected beyond their corresponding uprights, the lintel over the outermost shakha takes a curvature on the top to make space for the river goddesses (?). The river goddesses, Ganga and Yamuna, are shown standing under a tree and over a makara. While Ganga is generally shown standing over a makara, Yamuna is shown over a kachchhapa (tortoise). The question, therefore, is whether the females over the lintel depict the river goddesses or not. Generally, there are other instances in Gupta art where this space is taken up by the river goddesses as seen in the Kankali Temple at Tigwan, however at Tigwan Yamuna is shown standing over a kachchhapa. In addition, Cave 5 has the sculptures of Ganga and Yamuna showing them standing over their respective vahanas. This proves the iconography of the river goddesses was already defined by this time and thus the females over this entrance door are not the river goddesses but they may be water nymphs or shalabhanjikas unless we agree that the sculptor made a grave mistake and carved a makara instead of a kachchhapa for Yamuna. The lintel for this shakha has fourteen three-dimensional bosses carved with a human head. The lintel above it has three chandrashala arches. Williams considers the decoration over the entrance doorway as well as its dvarapalas as a later addition explaining that the dvarapalas of this cave are the copies of the ones over Cave 7 as these figures are less integrally related to the door of the cave and thus it is very possible that they were added after the jambs had been carved and the facade smoothed off leading the figures to be sunk within the recessed panels. This appears ineptitude of a copyist, not of a beginner, who was employed by the Sanakanika patron and tried to copy the style of the royal carver of Cave 7.44

Ganesha, carved here with two arms, sits in lalitasana-mudra over a stool with his one leg hanging. He is depicted as ithyphallic and with a third eye, the latter is unusual in the case of Ganesha. In his left arm, he carries a bowl of modaka. His coiled trunk is trying reach to his left tusk. On the left and right of the entrance door, beyond the dvarapalas, are two images of Vishnu. In both these images, Vishnu is shown standing in sambhanga (equipoise) with two hands placed over his waist or on the projected sash of his waistband. The other two hands rest over his two weapons, gada (club) and chakra (discus), in the case of the right side image, these weapons are depicted in ayudhapurusha forms, gada as the female Kaumaudki and chakra as a male Sudarshana. Vishnu on the proper left has a srivatsa mark, a rare feature during the Gupta period.

Mahishasuramardini stands with her right foot placed over Mahishasura’s head and her left foot firmly placed over the ground. She held the hind body and the tail of the demon in her two left arms and the trishula held in her right hand pierced through the body of the demon. The attributes held in her multiple right arms are a garland, a sword, a vajra (thunderbolt), an arrow, and a bell. The attributes in her multiple left arms are a garland, a shield, a bow, and an unidentified object. There is confusion over the unidentified object which is carved in a canonical form similar to a folded umbrella made of feathers. Williams mentions such objects are seen frequently in the reliefs of Borobudur where these are held by attendants.45 The possibility of an attendant in this sculpture can be easily ruled out as there is no space. In fact, the sculptor had to compromise on space as some of the attributes, i.e. arrow and vajra, have been carved beyond the niche boundaries marked for the sculpture. Dass identifies this with a quiver.46 Another controversial object is the one held by the left and the right uppermost arms of the goddess. Banerjee identifies it as a godha or crocodile, V S Agrawala as a bowl, and Vogel as a servant.47 It was Harle who correctly identifies it as a garland. Williams says this twelve-armed form of Devi and the position of the buffalo with its head trodden by the goddess’s foot is unprecedented and being constructed upon parallel axes, this sculpture is one of the most impressive early Gupta carving at the site.48

Next to the left of Mahishasuramardini is an image of Kartikeya and then a cell with images of matrkas. There are a total of eight figures, two on the lateral sides and six in the rear. However, Harper counts seven figures on the rear wall stating only the legs of the first figure and one leg of the last figure remains, the rest of the figures are better preserved with their torso and heads still visible.49 Dass counts only six figures on the rear wall and suggests that they represent six of the sapta-matrka group.50 The first figure on the left has a broad chest and thick neck whom Harper identifies as Shiva and Dass as Virabhadra. Another male figure is on the right lateral wall however that figure is much effaced and beyond recognition.

At a right angle to the cave is a cavity, 8.5 feet in length and 3 feet deep.51 On the left lateral wall is a figure of standing Kartikeya. Eight images are carved on the rear wall, all shown seated in lalitasana-mudra. Above the heads of all the figures are carved their emblems. Harper suggests the first figure appears that of Shiva however, his emblem is no more recognizable.52 The second figure has some circular object as her emblem, similar to the case of Cave 4, and she might be Brahmani. The next figures are that of Maheswari with trishula, Kaumari with shakti (spear), and Vaishnavi with chakra (discus). The next three emblems are not very clear however, they might represent Varahi, Indrani, and Chamunda thus completing the group of sapta-matrkas. The tenth and last figure is carved on the right lateral wall. However, this figure is much damaged and is beyond recognition. A faint outline of a spear is still visible and thus he may be Kartikeya or a guardian. Dass takes the eight figures over the rear wall to represent ashta-matrka group comprising the sapta-matrka and Yogeshwari.53 The rock face next to the cell is carved with the images of Ganesha, and Mahishasuramardini, both much defaced.

Inscriptions:

- Above the image of Vishnu and Mahishasuramardini, on the face of Cave 654– written in the characters belonging to the southern class of alphabets, language Sanskrit – refers to the reign of the Gupta king Chandragupta II and mentions the year 82, taking it as the Gupta Era, the inscription can be dated to 401-02 CE – the translation goes, “Perfection has been attained! In the year 80 (and) 2, on the eleventh lunar day of the bright fortnight of the month ashadha, – this (is) appropriate religious gift of the Sanakanika, the maharaja …….dhala (?), – the son’s son of the maharaja Chhagalaga; (and) the son of the maharaja Vishnudasa, – who meditates on the feet of the Paramabhattaraka and maharajadhiraja, the glorious Chandragupta (II).”

- To the left of this inscription is an inscription in Telugu language, it has yet to be published.

Cave No 7 (Tawa Cave) – Cunningham mentions this cave is locally known as Tawa Cave because of a large flat stone resembling a tawa (griddle) that crowns the cave chamber. The chamber is about 14 feet long and 12 feet wide.55 An inscription at the rear wall mentions it was excavated by Saba Virasena, a minister of Chandra Gupta II. The only decoration inside the chamber is over the ceiling consisting of a lotus motif. Williams mentions it is generally assumed that the Cave 6 inscription precedes Cave 7, but stylistic examination of these two caves suggests that the relationship between the carvings of the two doors is the reverse. Though the dvarapala images over the entrance are much damaged, however, their affinity to a few Mathura-style images indicates that the donor, Saba Virasena, employed carvers who were fully aware of the current styles of such metropolitan centers as Mathura.56 The inscription on the rear wall is not in the center but placed in a corner. Dass takes cognizance of it and explains the reason behind it may be because the main focus element was the iron pillar that once stood in the front. To keep the focus on the pillar, this inscription was engraved not in the center but in one corner. She fits this theory to support her hypothesis that the famous Iron Pillar standing in the Qutb Minar Complex at Delhi was originally installed in front of this cave, a theory first proposed by R Balasubramaniam and later on developed by both scholars together. While we cannot comment on this theory at this juncture, however, the reason for the placement of this inscription may be that the image that once adorned this cave was installed in the center and therefore the inscription had to be shifted.

Inscriptions:

- On the rear wall of the cave57 – written in the northern class of alphabets, the language is Sanskrit, no date mentioned – The inscription describes Chandragupta II as shining like the sun upon the earth and radiant with internal light. Then it mentions Saba Virasena, who got the ministerial position by his hereditary descent, belonging to the Kautsa gotra, and an expert on shabdartha (word meaning), nyaka (logic), lokagyana (knowledge of mankind), and poetry. He was a resident of Pataliputra and came to Udayagiri with King Chandragupta II, while the latter was on his journey to conquer the world. Saba, through his devotion to God Shambu, caused this cave to be made.

Cave No 8 – From the side of the previous cave starts a passage running 100 feet and crossing across the hill. Various figures and excavations are carved on both sides of this passage, over the rock face. Cave No 8 is a shallow cell in the rock face, measuring about 11 feet in length and 2.5 feet in depth. Its rear wall was prepared for further work however no sculpture was attempted.

Cave No 9 – This cave has an entrance doorway consisting of three shakhas (bands). These shakhas are devoid of any decoration and also do not form a T-shaped design over their lintel. The chamber measures about 4 feet long and 3.5 feet wide.58 Inside the chamber is an image of Vishnu hewn out of rock. The head of the image is chiseled out leaving its outline. On either side of Vishnu are standing his ayudhas in anthropomorphic form, on his right is Kaumaudki-gada, and on his left is Sudarshan-chakra. His two hands are placed over these ayudhas and the other two are over his waist.

Cave No 10 – The entrance of the cave is guarded by dvarapalas. The chamber measures about 3 feet long and a little less than 3 feet wide.59 Inside the chamber is an image of Vishnu. He stands in sambhanga-mudra (equipoise) keeping his two lower arms over the anthropomorphic images of his two ayudhas, on his right is Kaumaudki-gada, and on his left is Sudarshan-chakra. Contrary to other similar images of Vishnu at the site, here ayudha-purushas are shown seated with one folded leg and joined hands in anjali-mudra. His two upper hands are placed over his waist. He wears a long garland reaching a little below his knees. Over his head is a tall mukuta.

Cave No 11 – This cave is a small chamber measuring 4 feet 3 inches long and 3 feet 3 inches wide.60 Over the rear wall is carved an image of Vishnu. He stands in sambhanga-mudra (equipoise) keeping his two lower arms over the anthropomorphic images of his two ayudhas, on his left is Kaumaudki-gada, and on his right is Sudarshan-chakra. Contrary to other similar images of Vishnu at the site, here ayudha-purushas positions are reversed. His two upper hands are placed over his waist. He wears a long garland reaching a little below his knees. Behind his head is an oval halo.

Cave No 12 – This cave is a series of small open niches. In the first two niches are carved an image of Vishnu, now much defaced. These images are in the same style where he stands in sambhanga-mudra with his two lower hands placed over his ayudhas, the latter are sometimes represented in their anthropomorphic form. He wears a long garland that reaches a little below his knees and his upper two hands are placed over his waist. In one image here we see ayudha-purushas while in another they are in their weaponry shape. The larger niche in the series has a sculpture of Vishnu as Narasimha. Below this niche, on either side, is carved an image of a dvarapala. He is also carved in the same style as the other standing Vishnu images at the site. His ayudha-purushas are standing next to him on either side. Dass opines that the two large panels, that of Varaha and of Vishnu-Anantasayana, and this Narasimha sculpture in between those two panels represent the three different aspects of a kalpa. In Indian mythology, the creation and destruction of the universe is a repeating activity of Brahma. A day and night of Brahma corresponds to one cycle of creation and destruction of the universe. The day and the night are of the same length, equalling a kalpa. Brahma starts his day at dawn and his activity of creation continues till dusk, at the end of which he dissolves the universe. Then starts the night of Brahma when he takes rest. Thus, at the start of the day and the end of the day, the creation remains dissolved into a cosmic ocean. Dass compares the rescue of Bhu-devi from the ocean to the start of the day of Brahma, thus representing dawn. She takes the Vishnu-Anantasayana as the sleep of Brahma, after the dissolution of his creation, during the night. The Narasimha image placed in between these two sculptures represents the dusk when the day meets the night. She tells Narasimha emerged from a pillar during dusk as demon Hiranyakashipu was given a boon that he could not be killed during day or night. And this fits very well with the overall theme when we see these three panels combined.61

Cave No 13 – Like a few preceding caves, this is also an open-cell cave housing a 12 feet long image of Vishnu in his Anatasayana form. He lies, with his feet in the west, over the colossal coils of Shesha with various different figures carved around him, above and below. V S Agrawala has satisfactorily identified these various figures referring to the description provided in the Devi-mahatmya. Above the figure of Vishnu are eight figures. From left to right, these are Goddess Tamasi (sleep or nidra), Brahma seated over a lotus, Garuda, and three ayudha-purushas, Kaumaudki-gada, Sudarshan-chakra, Panchajanya-shankha, and at the end two demons, Madhu and Kaitabha. He identifies the kneeling figure below Vishnu with sage Markandeya.62 Vishnu sleeping over a naga (snake) is sometimes taken as a political allegory as explained by Dass. She tells this icon may represent the victory of Samudragupta over the Naga dynasties as claimed in his Allahabad Pillar Inscription. This icon may also be relevant for Chandragupta II as he married a Naga princess.63 We have already discussed another theory of hers where she compares Vishnu-Anantasayana as representing the cosmic sleep of Brahma. In her short summary on the astronomical bearing of the site, she suggests that the direction of Vishnu’s feet to the west was part of a scheme where the summer equinox was announced when the sun rays touched the feet of God.64 This means that the people who carved this image had a very good understanding of the summer equinox as they were able to pinpoint the exact spot where to carve God’s feet. If they were having such a sound understanding and knowledge of this astronomical phenomenon then why take the effort to carve an image just to announce the summer equinox as they should anyway be able to predict this occurrence?

Willis takes water and time as the core leitmotifs at Udaigiri.65 He tells the rock surface of the passage shows significant water-worn signs, indicating the passage served as a water cascade. The water for this was brought from a large tank at the head of the passage, however, the precise channel through which water used to enter the passage is obscured by time leaving only traces.66 His claim that the non-uniformity of steps over this passage had an inherent or intentional purpose appears a little far-fetched as uniformity in carved steps over a long passage of over 100 feet in length is something little too much to expect. He further suggests that the image of Vishnu represents him in the sleep that he was put into at the start of the monsoon, the event usually celebrated during the varshamasavrata festival. He claims the position of this image, observance of the summer solstice, and the date of the inscription in Cave 6, all prove that this festival of varshamasavrata was celebrated during the Gupta period at the arrival of the monsoon. He identifies the large figure shown kneeling in front of the lord as Chandragupta II who, he claims, reverently puts the god to sleep. He takes into reference a few inscriptions in which the Gupta kings have been compared with the moon and states there are enough good reasons for likening Chandragupta to the moon and for identifying the tableau as a commemorative sculpture representing a special religious performance by the king.67

Willis states that Varaha, Narasimha, and Anatasayana can be linked in various ways: the flow of water and the position of water bodies, through the annual cycle of seasons and its ritual re-enactment, through the passage of cosmic time and the mythic events marking that time. He concludes that the material is enough to show that Anatasayana is the theological starting point for the iconographical program at Udaigiri and Varaha represents its culmination and the end point.68 Willis and Dass carried out their study together and published their thesis in different years. From their studies, it is very clear that the site does not have one definitive iconographical program as they were able to fit their theories into different themes, though not all themes fit convincingly, indicating there was not a single thread connecting these various images.

Cave No 14 – It is an empty cell measuring 7 feet by 7 feet. Cave No 15 is also an empty cell measuring 4 feet by 4 feet.69

Cave No 16 – Entrance is provided through a rock-cut doorway, jambs of which are devoid of any decoration. The chamber is 6 feet 9 inches square and has a pedestal with a hole in the middle suggesting it has a shiva linga inserted into the hole.70

Cave No 17 – This is numbered eighth in Cunningham’s account. The chamber measure about 11 feet by 10 feet.71 The entrance doorway has five shakhas (bands). The decoration over those is much eroded. The last shakha is a pilaster with a bell capital on the top. The upper portion of the doorway, where lintels join uprights, is much damaged. From what remains, it is clear that the doorway probably did not follow the T-shape pattern. However, the last shakha on the top has a sculpture panel having a human figure inside. This place is generally reserved for the river-goddesses however here we find a male figure. These figures may not be dvarapalas as they are found near the base of the doorway on either side. These dvarapalas carry a spear, which may be trishula, and therefore the cave may be dedicated to Shiva. Two large sculptural panels are provided on either side of the entrance.

The panel on the right has a twelve-arm image of Durga as Mahishasuramardini. She holds a garland in her upper two hands and in her other hands, she holds an arrow, trishula, bow, a shield, and an unidentified object. She holds the buffalo demon in her three hands, one hand holding its mouth, one its tail, and the third hand placed over its back. She is accompanied by an attendant standing on her left. The panel to the left of the entrance has an image of Ganesha. He is shown as ithyphallic and four-armed. Cunningham and Patil mention a Shiva linga inside however only its pedestal remains at the site. A broken image of a lion is presently placed over this pedestal. Patil also mentions a damaged figure of a bull lying outside the cave, which is also no more at the site.

Shankha-lipi Inscriptions – James Princep named this script Shell script because of the letter shapes and style having similarities to the form of a shell or shankha (conch). The script has not been satisfactorily deciphered till now except for a few letters. There are many such inscriptions at Udaigiri, most of these are engraved over the rock face of the passage. These inscriptions are speculated to be names or signatures. Dass tells the script seems much more closely associated with the Gupta period and it appears mostly on the sites where the temples of the Gupta period were found.72 In a few places, i.e. the Narasimha image, sculptures are carved over the inscriptions suggesting the sculptures are of the later period. As these inscriptions are mostly over the rock face of the passage, this suggests that the passage held an important cultural and religious status. Dass mentions there are five different calligraphic styles at Udaigiri suggesting different people at different periods occupied the site before the arrival of the Guptas.

Cave No 18 – This cave is a cavity in the rock face where a sculpture of Ganesha has been carved out. Ganesha is sitting in lilasana-mudra, has four hands, and is shown as ithyphallic. In his hands, he carries a rosary (akshamala), pharasu (axe), and a plate of modaka (sweetmeats). He is accompanied by an attendant carrying a banana tree.

Cave No 19 – This cave is numbered nine in Cunningham’s account and is named Amrita Cave because of the scene of amrita-manthan carved on its doorway. It is the largest cave in the complex, measuring 22 feet long and 19.5 feet wide.73 The ceiling of the cave chamber is supported by four rock-cut pillars dividing the roof into nine compartments. The entrance doorway follows the T-shaped Gupta period style and consists of three shakhas (bands). The lintels over the jambs are extended beyond uprights thus forming a T-shape. The external most shakha has dvarapalas at the base and river goddesses at the top near the lintel, over its extended ends. The river goddesses, Ganga and Yamuna, are shown standing under a tree. This shakha culminated over the lintel with Gaja-Lakshmi (?) in the center. The middle shakha has female figures at the base, the figure on the left carries a vessel and the figure on the right carries a lotus stem. They are shown standing under a tree and accompanied by a dwarf attendant. The jamb above these figures has three sculpture panels with intervening floral bands.

At the top are vyala riders over the extended ends of the lintel. The arrangement of sculpture panels intervening with floral bands continues over the lintel except for the central lalata-bimba part which is left uncarved. The innermost shakha is continuously decorated with floral designs over the jambs and the lintel parts. A sur-lintel over the third shakha has a scene of amrita-manthan, much damaged however enough remains to provide details of the theme. The architrave above the sur-lintel is said to be carrying images of Nava-grhas as reported by Cunningham however these images are no more visible.74 The cave has a mandapa in the front, only the pillars have survived. The roof of the mandapa was supported by four pillars providing three entrances.

Inscriptions: There are a few inscriptions engraved over the pillars inside the cave.

- On the north face of a pillar on the left75 – written in eight lines, Nagari characters, Sanskrit language dated Vikarama Samvat 1093, equivalent to 1036-37 CE – “Obesiance! Kanha, the glorious restorer of that which has decayed, bows forever to the feet of Vishnu. The year 1093 after the reign of Vikramaditya. The temple was made by Chandragupta.”

- From the inscriptions, Willis draws a parallel stating that Chandragupta’s epithet Vikramaditya indicates that Chandragupta drew an analogy between his own acts as king and Vishnu’s trivikrama, three strides of Vishnu in which he conquered the earth and the heaven. The requisite link between Vikrama and Aditya is provided by the association of Vishnu’s three strides with the position of the Sun at dawn, midday, and sunset.76 Willis also states that the worship of Vishnu’s feet or Vishnupada was prevalent during the reign of Chandragupta and the latter put special emphasis on this worship mode. There are various issues with this theory of Willis. The first issue is that Kanha is mentioned as bowing forever to Vishnupada however there is no indication of whether Vishnupada was the cult object inside the cave. The inscription plainly mentions Kanha restored the decayed shrine but what was the cult object is a topic of speculation. The inscription does not equate Chandragupta with Vikramaditya, the latter is only used as an era in which the year is mentioned. Chandragupta II had an epithet Vikramaditya, however, the inscription does not provide any information to form a basis or explanation of that epithet.

- On a pillar inside cave 1977 – written in three lines, Sanskrit language, Nagari characters, undated – the inscription may be assigned to the eleventh century CE on the basis of paleography – “A plot (nivartana) in the village of Maniyaraka [was given] by rajaputra Sodha.”

- Above the previous record78 – written in three lines, Sanskrit language, Nagari characters, undated – the inscription may be assigned to the eleventh century CE on the basis of paleography – “A plot (nivartana) [of] mahasamnta Somapala.”

- On a pillar79 – written in two lines, Sanskrit language, Nagari characters, undated – the inscription may be assigned to the eleventh century CE on the basis of paleography – “Village land (pali) [was given] by rajaputra Vahiladeva.”

- On a pillar80 – written in two lines, Sanskrit language, Nagari characters, undated – the inscription may be assigned to the eleventh century CE on the basis of paleography – “[Given?] by rajaputra Damodara Jayadeva.”

Cave No 20 – This is a Jain cave consisting of four rock-cut sculptures, two on either side of the entrance. The Tirathankaras are shown seated over a pedestal with a wheel in the middle and devotees on either side. The cave is dedicated to Parshvanatha.

Inscription:

- Inside Cave 2081 – Northern class of alphabets, Sanskrit language – the inscription refers to the period of the Early Gupta kings but does not mention any specific king, based upon the recorded year 106, it is generally taken to the time of the Gupta king Kumargupta (415-455 CE) – the inscription mentions Samkara, who adhered to the path of ascetics. He was a disciple of Acharya Gosarman, and the son of Padmavati and Sanghila. He was born in the northern countries resembling the land of North Kurus. He caused to be made a sculpture of Parshvanatha richly endowed with the expanded hoods of a snake and an attendant female deity, in the mouth of the cave.

Ruined Gupta Temple – Nothing is left of this ruined temple at the site. Dass mentions a stump of a column lying in front of the ruined temple is at its original location as observed by her. The broken shaft was found lying near the stump and was later set up right next to the stump. Dass opines that the column was topped by the Four-Lions capital that was found lying in front of Cave 19 and is now housed in the Gujari Mahal Museum, Gwalior.82

The abacus of the capital has images of twelve rashis (zodiac signs) interspersed with twelve Adityas, one Aditya intervening between two rashis. As a portion of the abacus is broken, we are only left with figures of seven Adityas and nine rashis. Adityas are seated on a stool with a disc behind each figure. A few of the carry a water jar, and a few other objects. The rashis are shown with the human figure and animal heads. Among the surviving rashis are dhanusha (Sagittarius) shown as a male figure holding a bow, makara (Capricorn) shown with a male figure with a makara-head, kumbha (Aquarius) shown as a male figure holding a bowl, meen (Pisces) shown as a male figure with a fish-head, mesha (Aries) is a much-obliterated figure, vrshabha (Taurus) shown as a male figure with a bull-head, mithuna (Gemini) shown as a couple, karka (Cancer) shown as a male figure with a crab-head, and Simha (Leo) shown as a male figure with a lion-head. Four addorsed lions, one each in the cardinal direction, are surmounted above this abacus. The three dots separate each pair of Aditya and rashi and are sometimes taken to represent stars as the overall arrangement has astronomical significance. Williams takes the view that the capital was originally a Maurya period piece and was later modified during the Gupta period of the sixth century CE. She explains that except for the figures over the abacus, the rest of the piece was left unaltered by the Gupta sculptors leaving a part of polish over the legs of lions.84 The recut of the abacus during the Gupta period and the carving of astronomical deities suggest that the Gupta artists attempted to fit the capital into the new theme of the hill, an astronomical observatory. We will discuss this in detail later in the article.

Single Lion Capital – This single lion figure capital was found by Cunningham during his explorations in 1875-76. It was acquired by the Gwalior Museum in 1927-28. Through Cunningham mentions this capital however he did not disclose any finding spot for the same. Dass was able to locate the original finding spot of this capital stating it was found on the topmost part of the passage running across the middle of the hill.83 The fragments of the shaft, on which this capital was mounted, are currently lying in the passage. The abacus has six animals, arranged in a procession, a winged tiger, an elephant, a double-humped camel, a winged horse, a winged griffin, and a bull. There are four circular holes on the rock ledge where the capital was located suggesting these were postholes for pillars that once supported the roof of a mandapa. A short distance from there is a mound, the probable spot where this pillar would have stood. About 10 m to the south is a much larger mound suggesting a temple as remains of an amalaka are found nearby. The dating of this piece is complex in the absence of an epigraph, however, it has been dated on stylistic grounds by various scholars. Williams dates this to the second century CE considering it as a Gupta-period sculpture, Dass takes it before the Heliodorous pillar (dated 80 BCE) suggesting it is the earliest surviving monumental sculpture in the region.85

Was Udayagiri an astronomical observatory – Dass and Willis have strongly asserted that Udayagiri was a site connected with astronomical observations and the site was in use prior to the arrival of the Guptas and continued being used after their departure. To support their hypothesis, they both put forward various postulates.

- Existence of a Surya temple and solar observations – Willis suggests the temple of Bhaillasvami, mentioned in an inscription found at Bijamandal in Vidisha, originally stood at the hill of Udayagiri as the inscription mentions Udayagiri. To further strengthen his theory, Willis takes into reference another inscription that mentions donations to Narayana and the divine mothers at Bhaillasvami. He tells this inscription makes clear the presence of Narayana and the divine mothers along with Surya and all these are found in different caves at Udayagiri.86 As Dass and Willis worked together at the site, Dass accepts Willis’ argument and tells the Sun worship was a prevalent practice before the Guptas at Udayagiri. She emphasizes that the Vaishnava imagery at Udayagiri is not separate from other aspects of the hill such as sun worship or astronomical observations and is an expression of conjoint ideas and thoughts. She suggests that the enlargement of the passage to form an angle of 51 to the north-south axis was part of the largest astronomical scheme, and so is the carving of Anantasayana’s feet to the west. The summer equinox was as if announced when the rays of sun touched the feet of the god asleep on his serpent bed.87 Willis made an observation that there were virtually no shadows in the passage throughout the day on the summer solstice as the passage is aligned to the Sun’s east-west path, a natural configuration of the site that seems to be the chief reason for its significance. He admits narrow shadows were cast by the southern wall when there should be none, and this he explains stating that the Tropic of Cancer now stands a few kilometers south of Udaigiri but it would have fallen over Udaigiri in the olden times. He further states that this fact about the movement of the Tropic of Cancer is well-known to astronomers but not generally appreciated. Without giving much detail, he asserts the main point, irrespective of the exact position of the Tropic, is that Udayagiri was a place where the summer solstice was observed and astronomical observations made.88 In support of his theory, he takes into account the Shell-script inscriptions engraved over the rock, stating the way the curving letters scroll over the whole surface lends magical properties to the site, tightening the feeling that the passage had long been a place of talismanic power.89 He goes further that it was not just the observance of solstices but the site was also used to determine months, days, fortnights, and time. For the measurement of time, Willis proposes the presence of a water clock.90

- The first problem with Willis’ argument is that the inscription he takes into account for the Bhaillasvami temple is an eleventh-century CE inscription. The inscription was first edited by D C Sircar and he tells the epigraph was extremely damaged with the right-hand side of the stone broken away and the writing of the lower lines completely obliterated. Sircar tells the mention of Udayagiri and ambara-chudamani in the first verse 1 suggests that it speaks about the Sun god.91 As the epigraph is extremely damaged therefore it is not clear in what context the word Udayagiri had been used and taking Udayagiri as a reference to the hill is contestable. Also, the epigraph was stored at Bhilsa (modern Vidisha) Dak Bungalow therefore its exact finding spot is not known.

- The second issue is with the solar observations. It is suggested that the hill was used for solar observations, especially equinoxes and solstices. And, the Gupta artists carved images in accordance with the solar observations, i.e. the feet of Narayana facing west. The experiments carried out by Dass and Willis do not concretely prove the alignment of the image was such that the image was under shadow for a certain period or the Sunrays fall over the feet on certain days, etc. To overcome this, Willis makes an argument that the Tropic of Cancer is not stable and keeps oscillating, and probably during the age of the Guptas it was nearer to the Udayagiri hill compared to where it is now. And if we apply this fix, then probably we might get the desired results in observations. Here again, the scholars take liberties in fitting their theories with their ideas. While Willis uses the Shell-script inscriptions as talismans to lend magical properties to the site, Dass says these Shell-script inscriptions are mostly signatures of people associated with the site or engravings. As the Shell-script inscriptions are not satisfactorily deciphered till now, we cannot be very clear on what they represent.

- Sculptural proofs – The abacus of the Four-Lions Capital depicting rashis (zodiacs) and Adityas is generally taken as proof of astronomical significance. It is generally accepted that the capital was originally made during the Mauryas and its abacus was recut during the Guptas. Why the Gupta sculptors carved rashis and Adityas is an interesting question, and it may be connected with some astronomical activities however it is the only sculptural piece connected with an astronomical theme. Willis mentions another sculptural piece connected to an astronomical theme. It is a broken piece of a lotus ceiling containing images of nakshtaras (constellations). This lotus ceiling might be part of a temple, and the depiction of nakshatras does not necessarily connect it to astronomical studies.

Political Allegory in Udayagiri sculptural panels – Political allegory in the Varaha panel was first suggested by K P Jayaswal stating the kneeling figure in front of the Varaha is probably Chandragupta II. Later, scholars elaborated on this hint and a few even suggested that Varaha represents Chandragupta II in an act of rescuing the earth from enemies. However, Dass’ attempt in equating the title vikrama with (tri)vikrama, stating that Chandragupta II’s epithet Vikramaditya indicates Chandragupta was drawing an analogy between his own acts as king and Vishnu’s Trivikramama, the heroic three strides by which Vishnu redeemed the world from evil forces, is little far-fetched.

Role of water in Udayagiri imagery – Examination of the tanks and water channels, no longer in use now, suggests that running water was deployed to amplify the impact of the sculptures and the settings. This created a transformation of an oral myth into a visual myth. However, this aspect of the site could not be fully explored by Dass as the key features were only partly visible and need to be exposed by excavation.92

1 Patil, D R (1948). The Monuments of the Udayagiri Hill. Alijah Darbar Press. Gwalior. p. 2

2 Dass, Meera I (2001). Udayagiri: A Sacred Hill, its Art, Architecture and Landscape, Ph. D. thesis submitted to the De Montfort University, Leicester, UK. pp. 27-28

3 Cunningham, Alexander (1880). Report of Tours in Bundelkhand and Malwa in 1874-75 and 1876-77, vol. X. Archaeological Survey of India. Delhi. pp. 46-56

4 Lake, H H (1914). Besnagar published in the Journal of the Bombay Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, vol. XXIII. pp. 135-146

5 Excavations at Besnagar published the Annual Report of the Archaeological Survey of India 1913-14. p. 186

6 Excavations at Besnagar published the Annual Report of the Archaeological Survey of India 1914-15. pp. 66-88

7 Dass, Meera I (2001). Udayagiri: A Sacred Hill, its Art, Architecture and Landscape, Ph. D. thesis submitted to the De Montfort University, Leicester, UK. p. 3

8 Dass, Meera I (2001). Udayagiri: A Sacred Hill, its Art, Architecture and Landscape, Ph. D. thesis submitted to the De Montfort University, Leicester, UK. p. 4

9 Jayaswal, K P (1932). Chandra-Gupta II (Vikramaditya) and his Predecessor published in the Journal of the Bihar and Orissa Research Society, vol. XVIII. pp 17-36

10 Patil, D R (1948). The Monuments of the Udayagiri Hill. Alijah Darbar Press. Gwalior.

11 Agrawala, V S (1945). Gupta Art published in the Journal of the U.P. Historical Society, vol. XVIII, parts 1 & 2. p. 134

12 Agrawala, V S (1977). Gupta Art. Prithivi Prakashan. Varanasi. p. 30

13 Mitra, Debala (1963). Varaha-cave of Udayagiri – An Iconographic Study in the Journal of the Asiatic Society, Vol. V, 1963, Nos 3 & 4. pp. 99-103

14 Harle, J C (1974). Gupta Sculpture. Oxford University Press. Oxford. pp. 10-11

15 Williams, Joanna (1982). The Art of Gupta India – Empire and Province. Princeton University Press. New Jersey. ISBN 0691039887. p. 43

16 Willis, Michael (2001). Inscriptions from Uadayagiri: locating domains of devotion, patronage and power in the eleventh century published in the South Asian Studies, vol. 17. pp. 41-53

17 Dass, Meera I (2001). Udayagiri: A Sacred Hill, its Art, Architecture and Landscape, Ph. D. thesis submitted to the De Montfort University, Leicester, UK.

18 Willis, Michael (2009). The Archaeology of Hindu Ritual – Temples and the Establishment of the Gods. Cambridge University Press. New York. ISBN 9780521518741

Leicester, UK. p. 46

19 Dass, Meera I (2001). Udayagiri: A Sacred Hill, its Art, Architecture and Landscape, Ph. D. thesis submitted to the De Montfort University, Leicester, UK. pp. 27-29

20 Epigraphia Indica, vol. XXX. pp. 215-16

21 Dass, Meera I (2001). Udayagiri: A Sacred Hill, its Art, Architecture and Landscape, Ph. D. thesis submitted to the De Montfort University, Leicester, UK. p. 46

22 Williams, Joanna (1982). The Art of Gupta India – Empire and Province. Princeton University Press. New Jersey. ISBN 0691039887. p. 49

23 Dass, Meera I (2001). Udayagiri: A Sacred Hill, its Art, Architecture and Landscape, Ph. D. thesis submitted to the De Montfort University, Leicester, UK. p. 46

24 Dass, Meera I (2001). Udayagiri: A Sacred Hill, its Art, Architecture and Landscape, Ph. D. thesis submitted to the De Montfort University, Leicester, UK. p. 46

25 Patil, D R (1948). The Monuments of the Udayagiri Hill. Alijah Darbar Press. Gwalior. p. 10

26 Harle, J C (1974). Gupta Sculpture. Oxford University Press. Oxford. p. 10

27 Cunningham, Alexander (1880). Report of Tours in Bundelkhand and Malwa in 1874-75 and 1876-77, vol. X. Archaeological Survey of India. Delhi. p. 47

28 Cunningham, Alexander (1880). Report of Tours in Bundelkhand and Malwa in 1874-75 and 1876-77, vol. X. Archaeological Survey of India. Delhi. p. 47

29 Dass, Meera I (2001). Udayagiri: A Sacred Hill, its Art, Architecture and Landscape, Ph. D. thesis submitted to the De Montfort University, Leicester, UK. p. 79

30 Williams, Joanna (1982). The Art of Gupta India – Empire and Province. Princeton University Press. New Jersey. ISBN 0691039887. p. 86

31 Harper, Katherine Ann (1989). Seven Hindu Goddesses of Spiritual Transformation – The Iconography of the Saptamatrikas. The Edwin Mellen Press. New York. ISBN 0889460612. pp. 75-76

32 Dass, Meera I (2001). Udayagiri: A Sacred Hill, its Art, Architecture and Landscape, Ph. D. thesis submitted to the De Montfort University, Leicester, UK. p. 82

33 Cunningham, Alexander (1880). Report of Tours in Bundelkhand and Malwa in 1874-75 and 1876-77, vol. X. Archaeological Survey of India. Delhi. p. 48

34 Williams, Joanna (1982). The Art of Gupta India – Empire and Province. Princeton University Press. New Jersey. ISBN 0691039887. p. 43

35 Mitra, Debala (1963). Varaha-cave of Udayagiri – An Iconographic Study in the Journal of the Asiatic Society, Vol. V, 1963, Nos 3 & 4. pp. 99-103

36 Cunningham, Alexander (1880). Report of Tours in Bundelkhand and Malwa in 1874-75 and 1876-77, vol. X. Archaeological Survey of India. Delhi. p. 48

37 Jayaswal, K P (1932). Chandra-Gupta II (Vikramaditya) and his Predecessor published in the Journal of Bihar and Orissa Research Society vol. XVIII. pp. 33-35

38 Harle, J C (1974). Gupta Sculpture. Oxford University Press. Oxford. p. 11

39 Dass, Meera I (2001). Udayagiri: A Sacred Hill, its Art, Architecture and Landscape, Ph. D. thesis submitted to the De Montfort University, Leicester, UK. p. 74

40 Willis, Michael (2009). The Archaeology of Hindu Ritual – Temples and the Establishment of the Gods. Cambridge University Press. New York. ISBN 9780521518741. pp. 58-59

41 Williams, Joanna (1982). The Art of Gupta India – Empire and Province. Princeton University Press. New Jersey. ISBN 0691039887. p. 45

42 Harle, J C (1974). Gupta Sculpture. Oxford University Press. Oxford. p. 10

43 Cunningham, Alexander (1880). Report of Tours in Bundelkhand and Malwa in 1874-75 and 1876-77, vol. X. Archaeological Survey of India. Delhi. p. 49

44 Williams, Joanna (1982). The Art of Gupta India – Empire and Province. Princeton University Press. New Jersey. ISBN 0691039887. p. 41

45 Williams, Joanna (1982). The Art of Gupta India – Empire and Province. Princeton University Press. New Jersey. ISBN 0691039887. p. 43

46 Dass, Meera I (2001). Udayagiri: A Sacred Hill, its Art, Architecture and Landscape, Ph. D. thesis submitted to the De Montfort University, Leicester, UK. p. 87

47 Dass, Meera I (2001). Udayagiri: A Sacred Hill, its Art, Architecture and Landscape, Ph. D. thesis submitted to the De Montfort University, Leicester, UK. p. 103

48 Williams, Joanna (1982). The Art of Gupta India – Empire and Province. Princeton University Press. New Jersey. ISBN 0691039887. p. 43

49 Harper, Katherine Ann (1989). Seven Hindu Goddesses of Spiritual Transformation – The Iconography of the Saptamatrikas. The Edwin Mellen Press. New York. ISBN 0889460612. p. 77

50 Dass, Meera I (2001). Udayagiri: A Sacred Hill, its Art, Architecture and Landscape, Ph. D. thesis submitted to the De Montfort University, Leicester, UK. p. 82

51 Cunningham, Alexander (1880). Report of Tours in Bundelkhand and Malwa in 1874-75 and 1876-77, vol. X. Archaeological Survey of India. Delhi. p. 50

52 Harper, Katherine Ann (1989). Seven Hindu Goddesses of Spiritual Transformation – The Iconography of the Saptamatrikas. The Edwin Mellen Press. New York. ISBN 0889460612. pp. 77-78

53 Dass, Meera I (2001). Udayagiri: A Sacred Hill, its Art, Architecture and Landscape, Ph. D. thesis submitted to the De Montfort University, Leicester, UK. p. 82

54 Fleet, J F (1888). Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum, vol. III. pp. 21-25

55 Cunningham, Alexander (1880). Report of Tours in Bundelkhand and Malwa in 1874-75 and 1876-77, vol. X. Archaeological Survey of India. Delhi. p. 51

56 Williams, Joanna (1982). The Art of Gupta India – Empire and Province. Princeton University Press. New Jersey. ISBN 0691039887. pp. 40-41

57 Fleet, J F (1888). Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum, vol. III. pp. 34-36

58 Patil, D R (1948). The Monuments of the Udayagiri Hill. Alijah Darbar Press. Gwalior. p. 16

59 Patil, D R (1948). The Monuments of the Udayagiri Hill. Alijah Darbar Press. Gwalior. p. 16

60 Patil, D R (1948). The Monuments of the Udayagiri Hill. Alijah Darbar Press. Gwalior. p. 17

61 Dass, Meera I (2001). Udayagiri: A Sacred Hill, its Art, Architecture and Landscape, Ph. D. thesis submitted to the De Montfort University, Leicester, UK. p. 76

62 Williams, Joanna (1982). The Art of Gupta India – Empire and Province. Princeton University Press. New Jersey. ISBN 0691039887. p. 47

63 Dass, Meera I (2001). Udayagiri: A Sacred Hill, its Art, Architecture and Landscape, Ph. D. thesis submitted to the De Montfort University, Leicester, UK. pp. 76-77

64 Dass, Meera I (2001). Udayagiri: A Sacred Hill, its Art, Architecture and Landscape, Ph. D. thesis submitted to the De Montfort University, Leicester, UK. p. 63

65 Willis, Michael (2009). The Archaeology of Hindu Ritual – Temples and the Establishment of the Gods. Cambridge University Press. New York. ISBN 9780521518741. p. 42

66 Willis, Michael (2009). The Archaeology of Hindu Ritual – Temples and the Establishment of the Gods. Cambridge University Press. New York. ISBN 9780521518741. p. 13

67 Willis, Michael (2009). The Archaeology of Hindu Ritual – Temples and the Establishment of the Gods. Cambridge University Press. New York. ISBN 9780521518741. pp. 33-36

68 Willis, Michael (2009). The Archaeology of Hindu Ritual – Temples and the Establishment of the Gods. Cambridge University Press. New York. ISBN 9780521518741. pp. 55-56

69 Patil, D R (1948). The Monuments of the Udayagiri Hill. Alijah Darbar Press. Gwalior. p. 17

70 Patil, D R (1948). The Monuments of the Udayagiri Hill. Alijah Darbar Press. Gwalior. p. 17

71 Patil, D R (1948). The Monuments of the Udayagiri Hill. Alijah Darbar Press. Gwalior. p. 17

72 Dass, Meera I (2001). Udayagiri: A Sacred Hill, its Art, Architecture and Landscape, Ph. D. thesis submitted to the De Montfort University, Leicester, UK. pp. 30-31

73 Cunningham, Alexander (1880). Report of Tours in Bundelkhand and Malwa in 1874-75 and 1876-77, vol. X. Archaeological Survey of India. Delhi. p. 52

74 Cunningham, Alexander (1880). Report of Tours in Bundelkhand and Malwa in 1874-75 and 1876-77, vol. X. Archaeological Survey of India. Delhi. p. 53

75 Willis, Michael (2001). Inscriptions from Uadayagiri: locating domains of devotion, patronage and power in the eleventh century published in the South Asian Studies, vol. 17. p. 42

76 Willis, Michael (2001). Inscriptions from Uadayagiri: locating domains of devotion, patronage and power in the eleventh century published in the South Asian Studies, vol. 17. pp. 42-43

77 Willis, Michael (2001). Inscriptions from Uadayagiri: locating domains of devotion, patronage and power in the eleventh century published in the South Asian Studies, vol. 17. p. 44

78 Willis, Michael (2001). Inscriptions from Uadayagiri: locating domains of devotion, patronage and power in the eleventh century published in the South Asian Studies, vol. 17. p. 44

79 Willis, Michael (2001). Inscriptions from Uadayagiri: locating domains of devotion, patronage and power in the eleventh century published in the South Asian Studies, vol. 17. p. 44

80 Willis, Michael (2001). Inscriptions from Uadayagiri: locating domains of devotion, patronage and power in the eleventh century published in the South Asian Studies, vol. 17. pp. 44-45

81 Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum, vol. III. pp. 258-260

82 Dass, Meera I (2001). Udayagiri: A Sacred Hill, its Art, Architecture and Landscape, Ph. D. thesis submitted to the De Montfort University, Leicester, UK. p. 143

83 Dass, Meera I (2001). Udayagiri: A Sacred Hill, its Art, Architecture and Landscape, Ph. D. thesis submitted to the De Montfort University, Leicester, UK. p. 38

84 Williams, Joanna (1973). A Recut Asokan Capital and the Gupta Attitude towards the Past published in Artibus Asiae, vol. 35, no 3. pp. 225-240

85 Dass, Meera I (2001). Udayagiri: A Sacred Hill, its Art, Architecture and Landscape, Ph. D. thesis submitted to the De Montfort University, Leicester, UK. p. 39

86 Willis, Michael (2001). Inscriptions from Uadayagiri: locating domains of devotion, patronage and power in the eleventh century published in the South Asian Studies, vol. 17. p. 48

87 Dass, Meera I (2001). Udayagiri: A Sacred Hill, its Art, Architecture and Landscape, Ph. D. thesis submitted to the De Montfort University, Leicester, UK. pp. 58-61

88 Willis, Michael (2009). The Archaeology of Hindu Ritual – Temples and the Establishment of the Gods. Cambridge University Press. New York. ISBN 9780521518741. p. 23

89 Willis, Michael (2009). The Archaeology of Hindu Ritual – Temples and the Establishment of the Gods. Cambridge University Press. New York. ISBN 9780521518741. p. 25

90 Willis, Michael (2009). The Archaeology of Hindu Ritual – Temples and the Establishment of the Gods. Cambridge University Press. New York. ISBN 9780521518741. p. 28

91 Epigraphia Indica vol. XXX. pp. 215-216

92 Dass, Meera I (2001). Udayagiri: A Sacred Hill, its Art, Architecture and Landscape, Ph. D. thesis submitted to the De Montfort University, Leicester, UK. p. 67

Acknowledgment: Some of the photos above are in CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain from the collection released by the Tapesh Yadav Foundation for Indian Heritage.