Nachna is a small village in the Panna district of Madhya Pradesh. The antiquity of the place was first brought to notice by Alexander Cunningham who visited the village in 1883-84 and after getting the names of the nearby villages, he named the site Nachna-Kuthara.1 However, the village is now known as Kachhgawan (कछगवां), and the adjacent village is known as Nachne (नाचने). R D Banerji was the next scholar who paid a visit to the site during his 1919 tour of central India in the capacity of the Superintendent, Archaeological Survey of India, Western Circle. His interest was aroused by the mention of a rock-shaped Gupta-period temple by O C Ganguly. While he explored the two known temples, in addition, he found the remains of four more temples in the jungle.2

The early political history of the village can be derived from the general history of central India. This region would have been under the Vakataks during the 4th-5th century CE. However, it appears that it was not ruled directly by them but by their feudatories, the Uchchhakalpas. An inscription found in the tank of the village, Nachna-ki-talai inscription, mentions a certain Vyaghraraja as a feudatory under the Vakataka king Prithivisena II (470-490 CE).3 Dubreuil suggests that Vyaghraraja of the inscription might be the Uchchhakalpa prince of the same name as mentioned in the various Uchchhakalpa inscriptions of Khoh and Karitalai area.4 The Uchchhakalpas ruled from their capital city of Unchehara located about 50 km from Nachna. Therefore, it might be very probable that Kachhgawan (Nachna-Kuthara) was ruled by the Uchchhakalpas. If accepted then it can be said that the allegiance of the Uchchhakalpas shifted from the Vakatakas to the Guptas during the later period of their rule as the successors of Vyaghra dated their inscriptions which is generally taking referring to the Gupta era. Taking the stock of the architectural wealth into consideration, Joanna Williams suggests that the village would have held an important position as a cultural and trade center, and perhaps was the capital of the Uchchhakalpas.5

Nachna holds a very important position in the art repertoire of the Gupta and later Gupta periods. Williams opines, “One aspect of the Nachna style that went beyond a simple continuity in workshop traditions is the inventive treatment of subject matter. This implies on one hand a receptivity o the part of craftsmen to sophisticated guidance, and on the other hand a lively local intelligentsia. It is this combination of elements, from minor motifs to general aesthetic, derived from a prestigious heritage and yet developing in new ways, that makes the remains of Nachna a vigorous finale to Gupta art. (sic)”6

Parvati Temple – The temple faces west and is dedicated to Shiva. Cunningham named it Parvati Temple as there was a larger temple nearby dedicated to Shiva therefore he may have assumed this smaller temple might be meant for Parvati. It is constructed on a high terrace and composed of a garbha-grha, and a pradakshina-path (circum-ambulatory). As the temple was provided with a pradakshina-path, this makes it the earliest surviving temple with this feature and thus falls under the sandhara category of temples. The garbha-grha is a square of 8 feet 10 inches and is surrounded by a 5 feet wide veranda on its four sides forming a pradakshina-path, the latter was once covered with a roof.7 Banerji mentions there was once a porch in front of the only entrance, the former has collapsed entirely.8 He further tells the outer walls of the temple, now what remains as the plinth of the temple, were carved to represent rocks with grottos, caves, and niches interspersed throughout the length. These caves were fitted with ganas (dwarves), lions, yakhas, warriors, boars, peacocks, monkeys, deer, and women. Meister explains that the major metaphors in the minds of Hindu temple architects were those of the body of the temple as a mountain and the sanctum as a cave and this temple falls under the rare category of style and design simulating mountainous environs with a garbha-grha in the center.9 While the plinth wall portion till the adhishthana (vedibandha) is constructed using dressed masonry, the portion above it is constructed using irregular shape stones looking very similar to natural rock formations. Many of the panels embedded into these cavities have been removed to the Tulsi Sangrahalaya (museum), Ramban (Satna) and a few are still in the sculpture shed at the site. Meister tells that the idea here was to represent Kailasa Mountain, the abode of Shiva. A parallel contemporary representation of the mountainous region is found in a 4th-6th century CE Krishna-Govardhanadhari panel, now in the Bharat Kala Bhavan, Varanasi. On the basis of a comparative analysis of its architectural style and sculpture, the temple has been dated to the last quarter of the 5th century CE, Williams classifies it between 480-500 CE.10

The garbha-grha of this flat-roofed temple is a two-story structure. An extra cell is raised over the regular square garbha-grha of the ground floor. As no means were provided to ascend to this upper cell, therefore, whether it was just a decoration element or had a religious purpose is not certain. The upper story is now left with its bare minimum remains, during the visit of Banerji, he tells a small flat roof was slightly raised in the center of the upper cell, and its roofing slabs were disturbed by a large tree standing nearby. It had two chaitya-shaped windows.11 The garbha-grha on the ground floor has plain walls with windows on each wall. The present shrine does not reflect the opulence of decor as of the original. Taking descriptions of the rear window from Cunningham, this window is now lying nearby in the grounds and the present garbha-grha is bereft of any window in its rear wall. The windows in the lateral walls, the windows were composed of vyalas with riders flanking a central pilaster, these windows were fitted into the mandapa of Chaumukhanath Temple sometime since 1918. Images of ganas were inset in the lateral walls as seen in the 1918 photographs, however, these gana panels are no more available or lost. The present window frames adorning the temple have niches at the bottom carrying ganas in various postures. An important two-armed image of Ganesha is found in the center of one such window, he is placed in the middle niche suggesting his ganapati stature. The garbha-grha doorway is composed of four shakhas (bands). Ganga and Yamuna are present at the base of the door-jambs. With them are present Shaiva dvarapalas accompanied by Trishula-ayudhapurushas. In the center of the lintel is Shiva-Vinadhara seated in maharaja-lilasana with Parvati. Two windows, having nagas motifs, that were once embedded into the front side walls of the temple are now embedded into the nearby Chaturmukha Mahadeva Temple, on either side of its garbha-grha doorway.

The temple had some of the earliest lithic Ramayana panels, a total of six in number. From the surviving panels, the story depicted is the forest dwelling of Rama, Sita’s abduction by Ravana, and the last panel shows Hanumana being brought to the court of Ravana. The first panel in the sequence depicts the scene of Sita’s dialogue with Lakshmana after Rama left for the golden deer. When the golden deer, impersonating Rama, cried for help, Lakshmana was not ready to leave Sita to go in search of Rama. The middle male figure with his hands over his ears represents Lakshmana when he closed his ears when Sita rebuked him for not helping his brother. The rightmost male figure, shown in the posture of moving out, is again Lakshmana who unwillingly left Sita in search of Rama. The next panel shows Ravana taking alms from Sita and it is of great importance for its exquisite style and design. The next three panels are related to the meeting of Hanuman with Rama and Lakshmana followed by a duel between Sugriva and Vali. In one duel panel, both Sugriva and Vali are indistinguishable however in the next panel Sugriva wears a long garland allowing Rama to identify him while the former draws his arrow. The last panel shows Hanuman tied up and brought into the court of Ravana. Taking note of the dimensions of these panels, Williams12 tells these panels might not have come from the rocky-shaped base of the Parvati Temple and dates these to 500-510 CE, while Seema Bawa13 opines that these were part of some lost Vaishnava temple.

Apart from these Ramayana panels, many sculptures were found in the vicinity and collected at the sculpture shed at the site and around the temple compound. Among these is a chaturmukha-linga that was found near Lakhorobagh and brought to the temple premises sometime between 1965 and 1969.14 It is suggested that linga of this type might be the prime object of worship in the Parvati Temple. A frieze showing seven planets with Rahu is among the earliest surviving example of ashta-grhas (eight planets). It was the period when Ketu was not yet considered among the planets. This frieze is no longer available at the site and has been lost sometime between 1965 and 1967.15

Chaturmukha Mahadeva (Chaumukhnath) Temple – This east-facing temple is presently in worship. Like the Parvati Temple, this temple is also constructed over a jagati (platform). It is composed of a garbha-grha, an antarala and a modern mandapa. The modern mandapa of the temple has been reconstructed sometime in 1918 utilizing decorative material from the nearby Parvati Temple. From the construction technique and utilized material, it is very evident that the present structure is not homogenous but comprised of materials coming from different eras, at least two distinct periods. R D Trivedi rightly says that at the time of construction of the temple, the architectural material of the earlier period was utilized in the formation of the bhadra-niches and the doorway with the flanking pillars.16 The temple is tri-ratha in plan till its jangha, and the shikhara above is in pancha-ratha style. The monument dates from the Pratihara period of the 9th century CE.

Banerji mentions the Bhadra-niches of the temple earlier had images of Vishnu, Shiva, and Durga. However, during the reconstruction of this temple, these images were removed and the bhadra-niches were fitted with perforated windows with two bands forming three spaces. These windows were originally part of an earlier temple that was replaced by this new structure. At the bottom of the bands in the windows, five panels are provisioned with images of ganas inside. The ganas are depicted in a playful mood and in various postures. The window in the west does not have figures of ganas but has a jewel design. Above the windows are two niches separated by pilasters. In all these niches are present vidyadhara couples, flying or standing. From the style and design, these windows appear to be part of the Parvati temple. The karna-niches (corner niches) were having ashta-dikpalas however, only two have survived, Agni in the south and Kubera in the north.

The garbha-grha doorway is very similar in style and execution to that of the Parvati Temple. The lintel is missing and Williams mentions a broken piece of lintel was embedded in the caretaker’s hut.17 The lintel bears an image of Shiva in its lalata-bimba. Williams dates the doorframe to 495-505 CE and it is evident this renovated 9th-century CE temple was built replacing a fifth-century Gupta period temple. The temple draws its name from the magnificent chaturmukhi-Shivalinga (four-faced linga). The face facing the entrance, or east, represents the Tatpurusha aspect of Shiva, while the face facing south represents Aghora, the face facing west represents Sadyojata, and the face facing the north represents the Vamadeva aspect. The Aghora face representing the terrific aspect of Shiva is beautifully carved with bulging eyes, wide open mount, and protruding teeth.

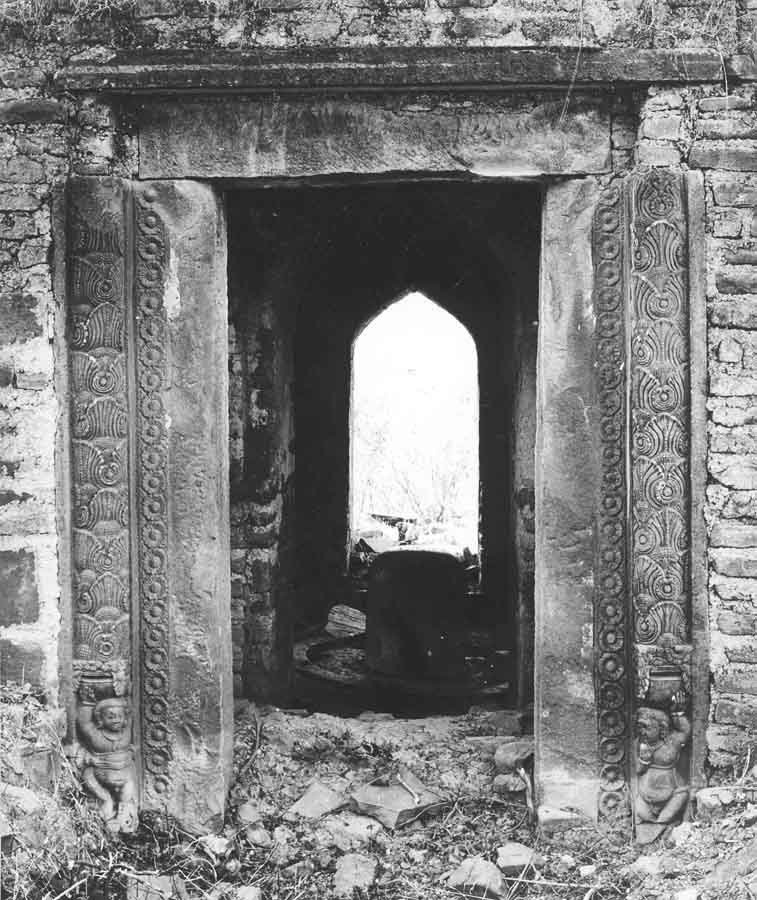

Telia (Taliya) Math (Kumra Math) – This ruined structure is located about 500 meters from the Parvati Temple complex. It is a fifteenth-century CE structure utilizing the material, especially the doorways, of an earlier structure, probably of the fifth-sixth century CE. The present structure has four entrances adorned with doorways on each entrance. Walter Spink18 suggests that these four doorways were part of an earlier four-sided shrine, however, Joanna Williams19 differs.

The southern doorway is the best preserved and provides details of its origins. On the terminals of its lintel are present two avataras of Vishnu contrary to the space occupied generally by river-goddesses or shalabhanjikas. Narasimha is shown grasping the demon Hiranyakashipu, the latter is on his feet trying to flee which appears useless at the moment. This posture is very different from the usual iconography where Narasimha is shown tearing the demon. Varaha on the other terminal is shown holding Bhu-devi. The figure of Bhu-devi is almost the same size as that of Varaha, and this again differs from the usual iconography of the icon where Bhu-devi is of very small size in comparison to the Varaha. The uppermost band of the lintel is decorated with a series of 29 human heads. Spink, stating he is not speaking with authority, mentions that it appears that the inner surrounds of this doorway were richly decorated however during the refitting of the doorway it was chiseled down so that painted motifs could be added.20 Williams seems right stating this large door frame surrounds another pair of lintel and jambs that were adorning the western side of the present structure however now removed to the Parvati Temple compound.21 She measures the parts and tells the position of chadrasalas of the two complement each other and thus were part of a single large doorframe. She tells this doorframe was once part of a Surya-Narayana temple as the image of the deity is present in the center.

The eastern doorway has only the door-jambs of the original and its lintel has been replaced with a plain beam. Decoration over two bands of the doorway is still intact, one band carries rosette molding and another carries floral decoration. The floral moldings are issued from a vase (purna-ghata) held above the head over a gana. One gana figure is no more available in situ, it appears broken or stolen.

The northern doorway is very different from the last two discussed doorways as it is bereft of original material. The present lintel over the door jambs is in fact a window (jali) of some lost temple that was lying nearby and utilized here. The door pillars were also part of that original temple however these would have been the pillars of a mandapa and are now utilized as doorway pillars. The western doorway has preserved better details of its original structure. At the base of the door jambs are Ganga and Yamuna over their respective mounts. Spink22 mentions the nearby fallen lintel belonging to this doorway having an image of Surya over its lalata-bimba.

Rupni Temple – The local legend says that Udal’s lover used to visit this temple to worship Shiva and thus the name Rupni’s temple. The present structure is, of course, a later period construction however its doorway is certainly a work of sixth-century CE. The river goddesses, Ganga and Yamuna, are present at the base of the door-jambs. Gaja-Lakshmi is present over the lalata-bimba however it would be tough to say whether the original temple would have been dedicated to Vishnu or Shiva as Gaja-Lakshmi is found in both types of temples. Panels over the door bands have niches carrying mithuna-couples. Williams23 dates the doorway to 530-540 CE.

Lakhurabagh – As per a local legend, the place was named after a king planting one lakh mango trees and feeding one lakh Brahmins. This led to a belief that the place had hidden riches under its soil making the locals dig and desecrate the ancient ruins it once had. Remains of these ancient riches, mostly pillars, and columns, are now embedded into a modern or later medieval dilapidated structure.

Jaina and other miscellaneous images – Over a dozen of Jaina Tirthankara images have been found at Nachna suggesting it was once an important Jaina center. Williams suggests that many of these Jaina images were sculpted during the latter half of the fifth century CE and the style of low ushnisha and small curls suggest that the sculptors came from Sanchi.24 A few images were installed in a cave on a nearby hill, then going by the name Siddh-ka Pahar and presently known as Shreyansh Giri Hill. Rupni Temple would once be a Jaina temple as suggested by Jaina images inside the shrine. Many broken images belonging to the Hindu pantheon are also found at Nachna, including that of Uma-Maheshvar, Vishnu, Lakulisa, Mahishasuramardini, and others. Many of these sculptures have been removed to Tulsi Museum, Ramvan. Hindu and Jaina cultures co-existed at many Gupta period sites and Nachna was one among those.

Inscriptions: Two important inscriptions are found in the village and its nearby Ganj village.

- Nachne-ki-talai inscription25 – not dated, refers to the rule of the Vakataka king Prithivishena II (460-480 CE) – language Sanskrit, box-headed variety of central India alphabet – This was discovered by Alexander Cunningham during his visit of 1883-84 in the tank of the village Nachna – reads, Vyaghradeva, who meditates on the feet of the Maharaja of the Vakatakas, the illustrious Prithivishena, has made (this) for the sake of the religious merit of (his) parents.

- Ganj Vakataka inscription26 – language Sanskrit, box-headed southern variety of characters – this inscription was discovered by R D Banerji in 1919 – reads, Vyaghradeva, who meditates on the feet of the Maharaja the illustrious Prithivishena, (of the family) of the Vakatakas, has made (this) for the sake of the religious merit of (his) parents.

1 Cunningham, Alexander (1885). Reports of a Tour in Bundelkhand and Rewa in 1883-84 and of a Tour in Rewa, Bundelkhand, Malwa, and Gwalior in 1884-85 vol. XXI. Archaeological Survey of India. New Delhi. pp. 95-99

2 Progress Report of the Archaeological Survey of India, Western Circle for the year ending 31st March, 1919. pp. 60-61

3 Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum, vol. III, pp. 233-35

4 Dubreuil, G Jouveau (1926). Vyaghra, The Uchchakalpa published in the Indian Antiquary vol. LV. p. 103

5 Williams, Joanna Gottfried (1982). The Art of Gupta India: Empire and Province. Princeton University Press. New Jersey. ISBN 0691039887. p. 105

6 Williams, Joanna Gottfried (1982). The Art of Gupta India: Empire and Province. Princeton University Press. New Jersey. ISBN 0691039887. p. 114

7 EITA p. 39

8 Progress Report of the Archaeological Survey of India, Western Circle for the year ending 31st March, 1919. p. 61

9 Meister, Michael W. (1986). On the Development of a Morphology for a Symbolic Architecture: India published in RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics No. 12. p. 35

10 Williams, Joanna Gottfried (1982). The Art of Gupta India: Empire and Province. Princeton University Press. New Jersey. ISBN 0691039887. p. 110

11 Progress Report of the Archaeological Survey of India, Western Circle for the year ending 31st March, 1919. p. 61

12 Williams, Joanna Gottfried (1982). The Art of Gupta India: Empire and Province. Princeton University Press. New Jersey. ISBN 0691039887. p. 113

13 Bawa, Seema (2018). Visualising the Ramayana: Power, Redemption and Emotion in Early Narrative Sculptures published in Indian Historical Review vol. 45. p. 96

14 Williams, Joanna Gottfried (1982). The Art of Gupta India: Empire and Province. Princeton University Press. New Jersey. ISBN 0691039887. p. 112

15 Williams, Joanna Gottfried (1982). The Art of Gupta India: Empire and Province. Princeton University Press. New Jersey. ISBN 0691039887. p. 113

16 Trivedi, R D (1990). Temples of the Partihara Period in Central India. Archaeological Survey of India. New Delhi. p. 127

17 Williams, Joanna Gottfried (1982). The Art of Gupta India: Empire and Province. Princeton University Press. New Jersey. ISBN 0691039887. p. 110

18 Spink, Walter (1971). A Temple with Four Uchchakalpa (?) Doorways at Nachna Kuthara published in Chhavi: Golden Jubilee Volume. Bharat Kala Bhavan. Banaras Hindu University. Varanasi. p. 162

19 Williams, Joanna Gottfried (1982). The Art of Gupta India: Empire and Province. Princeton University Press. New Jersey. ISBN 0691039887. p. 111

20 Spink, Walter (1971). A Temple with Four Uchchakalpa (?) Doorways at Nachna Kuthara published in Chhavi: Golden Jubilee Volume. Bharat Kala Bhavan. Banaras Hindu University. Varanasi. p. 166

21 Williams, Joanna Gottfried (1982). The Art of Gupta India: Empire and Province. Princeton University Press. New Jersey. ISBN 0691039887. p. 111

22 Spink, Walter (1971). A Temple with Four Uchchakalpa (?) Doorways at Nachna Kuthara published in Chhavi: Golden Jubilee Volume. Bharat Kala Bhavan. Banaras Hindu University. Varanasi. p. 167

23 Williams, Joanna Gottfried (1982). The Art of Gupta India: Empire and Province. Princeton University Press. New Jersey. ISBN 0691039887. p. 112

24 Williams, Joanna Gottfried (1982). The Art of Gupta India: Empire and Province. Princeton University Press. New Jersey. ISBN 0691039887. p. 105

25 Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum, vol. III. pp. 233-35

26 Epigraphia Indica vol. XVII. pp. 12-14

Acknowledgment: Some of the photos above are in CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain from the collection released by the Tapesh Yadav Foundation for Indian Heritage. Some of the photos above are in CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain from the collection released by Tapesh Yadav Foundation for Indian Heritage.

I have heard about this place but could not visit. I have enriched myself by going through this post.

the trouble it took to get there was certainly worth it wasn't it!

visited 1/05

Hi Kathie,

You are very correct, the whole trouble in getting was very much worth of. We have very few surviving temples from Gupta period, and this is one of those few.

Hi

dear thanks for such a nice information.i m very glad to see this site. the chaturmukh nath near in my village . so i m very happy .if u want to know about this place pleas visit us [email protected].

I am planning to visit in the coming weeks. How near is this to Maihar Mata? Could you also tell me in which tehsil of Panna it is? Devendranagar or Gunour?

It is little far from Maihar, but near to Sagar. I think it should come under Devendranagar tehsil but I am not sure.

Thanks a lot! Do you have a map which puts it relatively on to a route or a path?

Hi, I do not have its GPS coordinates, however it was very near to Saleha village.

Look out for Chaturmukhnath as these days it is popularly known with this name.

it`s lovely place

thanks for ur information

Comments are closed.