Eran (ऐरण) is a small village in the district of Sagar in Madhya Pradesh. The village is situated on the south bank of river Bina, a tributary of river Betwa. It is one of the most ancient towns in India and was known as Airikina, Erakaina, and Erakanya as evident from its epigraphs, seals, and coins. It was an important stop on the ancient routes connecting Pataliputra with Mathura passing through Vidisha. The earliest main route joined Kausambi to the south-eastern sea coast via Bharhut, Amarkantak, Malhar, and Dandakaranya forest. Another route from Kausambhi went in the south-western direction passing Bharhut, Eran, Vidisha, Ujjain, and Mahishmati to Bhragukachchha (Bharuch).1 T S Burt was the first modern explorer that brought Eran to the notice of scholars in 1838 after he reported the discovery of the Eran pillar. Alexander Cunningham was the first to notice the antiquities of Eran. He narrates a local legend assigning the foundation of the town to Raja Barat or Vairat. Bheem, a Pandava, during his exile came to this town. At the expiration of his terms of exile, he shot an arrow, named Kichak, in joy. This arrow, which was shot at a deer, instead hit the hoof of the cow, splitting it into two. However, the cow survived, its wound healed immediately and since then the hoof of all cows became cloven. Witnessing this event, the king came to know the real identity of the sojourner. Bheem left his gada and his mother’s churning stick and erected his own statue and left the town. The Garuda pillar at Eran is known as Bheem Gada, the other shorter column is his mother’s churning stick, and the statue of Vishnu as Bheem Sen as told by the locals to Cunningham.2

From the coins found in Eran by Cunningham, we find the old name of the town was Erakaya (एरकय) as written on those coins in Brahmi script of the second century BCE. In the later period inscriptions of the Gupta period, the name of the town is provided as Erikina (एरिकिण). Different scholars have provided different sources for the etymology of Eran. Cunningham opines the name of the town was derived due to the abundant growth of “Eraka (इरक)” grass.3 K P Jayaswal suggests that the republican coins of Eran proves the people were worshipper of Nagas and the town got its name after the Airaka, a Naga.4 The geographical limits of the town would have varied from time to time as it has been referred to as vishaya, bhukti, pradesh, nagar, and adhishthana in various epigraphs. Noticing the importance of the town, extensive excavations were carried out by K D Bajpai5, under the auspices of the University of Sagar, between 1960 and 1965. These excavations revealed various layers of settlement patterns taking back the antiquity of the town to the second millennium BCE. On the basis of stratigraphy, Bajpai classified the periods of settlement as stated below:

- Period I (Chalcolithic) – BCE 2000 – BCE 700

- Period II A (Early Historical) – BCE 700 – BCE 200

- Period II B – BCE 200 – 1st century CE

- Period III – 1st century – 6th century CE

- Period IV (Late Medieval) – up to 1800 CE

The most important finding of the period I was a mud defense wall and its associated moat. This wall suggests that the residents of the town were confined within the boundary marked by this wall. This wall served two purposes for the residents, first, it acted as a defense machinery as the town had the advantage of a natural barrier at its other three sides, being surrounded by river Bina. The second purpose this wall served was in form of a moat which was used to accommodate the access water in case of heavy rains, thus saving the town. The wall was 154 feet wide and 21 feet deep.6

Among the other significant findings, a circular lead piece bearing the name of king Indragupta, belonging to period II-A is the most important. A hoard of 3,268 punch-marked coins is among the most significant finding belonging to Period II-B. This hoard and the finding of other large numbers of coins suggest that Eran would have served as a mint during that period. Bajpai7 tells that before the conquest of the Guptas, Eran served as a mint minting coins for the local Naga rulers. Later these mints served the Gupta rulers. One copper coin, bearing the name of King Dharmapala, is counted among the earliest inscribed Indian coins, assigned to the third century BCE.8 An important finding of Period III is a clay seal depicting Gaja-Lakshmi icon with a Brahmi inscription. The site was excavated again between 1984-87 by Sudhakar Pandey and Vivekdutt Jha under the auspices of the University of Sagar and one more excavation work was carried out in 1998 by Vivekdutt Jha.

The early history of the town can be satisfactorily traced from the third-second century BCE after the fall of the Maurya empire when though the Shungas appeared as the dominant power, however, many regions got an opportunity to break themselves from the Mauryan yolk. Eran was one such region that came under the rule of a few independent rulers. Dharmapala appears to be the first such independent ruler that ruled over Eran as evidenced by his inscribed coins found by Cunningham. From an inscribed lead pipe discovered during excavations, we got Indragupta as another independent king of Eran. The third king was Shivagupta whose inscribed seals are found in Eran. Seals of Shivagupta are also found in Vidisha which suggests that he ruled over an extended area. As Indragupta and Shivagupta share the suffix Gupta, it is possible that both the rulers were connected and belonged to the same line of a dynasty, however, there is no sound proof to confirm the same.

The political history of Eran prior to the Guptas is not shrouded in clouds though it is clear that the region was under the Nagas and Sakas for a considerable period. From the coin-casts found at Eran, we come across four kings Vijaysen, Rudrasen (I), Vishvasingh, and Rudrasen (II), they may be the Saka kshatrapas ruling prior to the conquest by Samudragupta. A few coins are dated and we find Vijaysen was ruling in Saka 170 corresponding to 248 CE, and Rudrasen (II) was ruling between 258-267 C. Also, the rule of Nagas is attested by the discovery of various Naga seals. While many seals are worn out, the names of two Naga kings are clear, these are Ravinaga and Ganapatinaga. These two Naga kings are also found in the Naga dynasty line of Padmavati. Eran kept oscillating between the Guptas and the Sakas for a considerable period. During the beginning of the fourth century CE, Eran was under the rule of the Sakas who ruled through their kshatrapas. An inscription of a Saka king and Mahakshatrapa Sridharavarman has been found at Eran. As the inscription is dated in an unknown era, different scholars have different opinions on its dating. Mirashi9 takes the era as the Kalachuri-Chedi era and dates it to about 365 CE while Sircar10 takes the era as Saka and dated it to 279 CE. If we accept Mirashi’s dating, then as Sridharavarman ruled for at least twenty-seven years between 338-365 CE, it conflicts with Samudragupta’s (335-375 CE) rule over the Malwa region. As this seems improbable, therefore we may proceed with accepting Sircar’s dating of 279 CE. In this case, Sridharavarman could not be a contemporary of Samudragupta but his successor should be. Agrawal11 takes Balavarman as the successor of Sridharavarman and he was overthrown by Samudragupta. Another theory is that Samduragupta conquered Eran from the Naga kings rather than from the Sakas.12 This may be very much possible as from the epigraph of Saka Sridharavarman we find that a Naga individual erected a pillar at Eran for the prosperity of all people. This suggests that Nagas may be ruling as a feudatory under the Saka kshatrapas and Samudragupta might have fought with the Nagas as well as the Kshatrapa army.

A clay seal discovered at Eran mentions king Isvaramitra and his son Simhasena. Though it does not mention these kings as kshatrapas, however, Bajpai is convinced that the style of the inscription leaves no doubt that they were acting as kshatrapas. He says on the basis of paleography the seal cannot be placed after 350 CE and Simhesena of the seal cannot be equated with Swami Simhasena.13 However, at another place, he accepts Simhasena of the clay seal can be equated with Swami Simhasena, the latter ruling up to about 382 CE.14 If this is accepted then it is clear that though Samudragupta wrestled the Malwa region from the Sakas however the latter took it back soon after only to be finally overthrown by Chandragupta II. Simhasena would have wrestled the Eran region during or soon after Samudragupta however he did not rule very long as he was overthrown by Chandragupta II, the latter is credited as the exterminator of the Sakas and this takes the title ‘Sakari’. Bajpai suggests that the episode of a Saka king demanding the hand of the wife of Ramagupta, Dhruvadevi, may have happened at Eran as we find inscriptions of the Sakas as well as of the Guptas here.15 Ramagupta and Chandragupta II would have spent considerable time at Eran as evidenced by the variety and volume of their coins found at the site. Therefore Eran would be the place where the Sakas were exterminated by the Gupta king Chandragupta II. Mishra suggests Simhasena was the adversary of Ramagupta and Chandragupta, and he was the Saka king who demanded Dhruvasvamini.16

Eran was subjected to a foreign invasion once again during the Guptas, and this time it was the Hephthalites (Hunas of Sanskrit) who invaded the town during the waning period of the Gupta authority after the death of Budhagupta at the start of the sixth century CE. An inscription found in Eran mentions Toramana as maharajadhiraja and is dated to his first year of reign. This inscription, on a stone Varaha, refers to the erection of a temple by a Brahman Dhanyavishnu. The same Brahman is mentioned, along with his brother as the reigning king, in another inscription where the brothers, jointly, erected a Vishnu-pillar, in year 165 of the Gupta era, corresponding to 484 CE, during the reign of the Gupta king Budhagupta. As this pillar inscription does not mention Toramana, therefore it is assumed that Toramana captured Eran after 484 CE, probably around 500 CE.17 However, Toramana enjoyed this possession for a very short period of time. Another inscription at Eran, dated year 191 of the Gupta Era, corresponding to 510 CE, mentions the Gupta king Bhanugupta fought a battle though it does not mention his adversary. This battle might be fought against the Huna king Toramana either to defend against his invasion or to wrestle back the Gupta territories from him. Most probably it might be the case of recapturing the lost territories as from another inscription the Aulikara king, Prakashadharma, we come to know that he routed Toramana in about 515 CE.18 After the Guptas, the history of the town went into obscurity as it probably lost its importance while it remained part of the Malwa region, the latter was ruled by the Gurjara-Pratiharas, Rashtrakutas, Chadellas, Paramaras, and Kalachuris till the end of the twelfth century CE. We do not find any epigraph, except a few sati pillar inscriptions, of this intervening period that improve our knowledge related to Eran. A sati pillar inscription dated in Saka 1155 (1233 CE) mentions a king Maharajadhiraja Sujitanmahadeva who probably was ruling as an independent ruler over Eran.19 He was probably killed during the Muslim invasion and his wife became a sati. The Muslim rulers got Eran under their dominion in the latter half of the thirteenth century CE.

Epigraphs –

- Stone inscription of Samudragupta20 – written in Sanskrit – undated – This stone inscription slab was found by Alexander Cunningham near the Varaha temple and is now in the Indian Museum, Kolkata – The inscription mentions the Gupta king Samudragupta who is compared with Dhanada (Kubera) and Antaka (Yama) in joy and wrath respectively. A mention of setting up a temple of Janardana at Airikina to augment his own glories.

- Pillar inscription of Budhagupta21 – written in Sanskrit -dated in year 165 of the Gupta Era (484-85 CE) – The inscription opens with a verse in praise of Vishnu whose ensign is Garuda. Then we are told that when one hundred and sixty-five years had elapsed and when Budhagupta was the lord of the earth and when Surasmichandra was a protector of people protecting the province intervening between the Kalindi (Yamuna) and Narmada, this dhvja-stambha of Bhagwan Janardana was caused to be erected by the Maharaja Matrivishnu and his younger brother Dhanyavishnu, son of Harivishnu, grandson of Varunavishnu and above all the great-grandson of Indravishnu, the Brahmana sage, who was the head of the Maitrayaniya school of Yajurveda and performed sacrifices.

- Inscription on the neck of the boar22 – written in 8 lines in Sanskrit in Brahmi script – dated in the first reign of Toramana – The object of the inscription is to record the building of the temple in which the present Varaha statue stands, by Dhanyavishnu, the younger brother of the deceased Maharaja Matrivishnu. The inscription may be dated to 493-4 CE, the first known regnal year of Toramana.

- Stone pillar inscription of Bhanugupta23 – written in Sanskrit – dated in year 191 of the Gupta Era (510-11 CE) – This 2.5 feet tall linga was found by Cunningham on a high mound named Dana Bir. It was turned into a Shivalinga and was under worship when found – The inscription does not mention any reign of any particular king but mentions a certain Bhanugupta who might not be sovereign but some king of the Gupta family. The object is non-sectarian and mentions that in the company of Bhanugupta, who was a great ruler, his chieftain Goparaja came to Eran and fought a battle with the Maitras, and that Goparaja was killed, and that his wife accompanied him, by cremating herself on his funeral pyre, apparently near the place where the pillar was set up. This is probably the earliest record of the Sati tradition. Goparaja is stated as the daughter’s son of the Sarabha king.

- On the same pillar as no 424 – This inscription is a chance discovery by Krishna Deva in 1950-51 during his inspection tour. He found the last line of the Goparaja inscription was concealed under the pitha of linga, so he got these accretions removed and it brought up a new inscription in light. It is written in the Western variety of the southern alphabet and the language is Sanskrit. The inscription refers to the right of the king and Mahakshatrapa Sridharavarman, the son of Saka Nanda. The record is dated in the twenty-seventh regnal year of the king. The record has only survived in its two-thirds portion, this its complete description is not possible. The object of the inscription appears twofold, the first to record a construction by a person named Narayanasvamin, of a tirtha or stairs for a descent into the river at the adhishthana of Erikina in the territorial division Bahirika of the Nagendra ahara for the well being of the adhishthana headed by the cows and the Brahmanas as well as for the increase of the religious merit for the person’s parents. The second object is to mention the erection of a memorial pillar, called yashti by Satyanaga, the Arakshika, and Senapati of the Saka Mahakshtrapa and Raja Sridharavarman, at the same adhisthana for the removal of calamities, the attainment of prosperity and the happiness and wellbeing of all creatures. Satyanaga is described as a native of Maharastra and as a chief, apparently, of the Nagas. The Kankhera inscription of Sridharavarman is dated to the year 102, which was the thirteenth regnal year of the king, and taking this as the Kalachuri-Chedi era, Mirashi dates that to 351-52 CE. On this basis, the Eran inscription can be dated to about 365 CE. However, this dating is disputed and many scholars takes this date in the Saka era, thus year 102 corresponds to 279 CE

- Inscription on a small varaha statue, now in Sagar University25 – written in Sanskrit – undated, dated to 5th century CE on paleographic studies – This Nr-Varaha image was found by Cunningham in possession of a local Brahman in Eran who told the former that the image was brought from the location of the Buddhagupta pillar. A short inscription near the pedestal reads two names, Mahesvara-datta and Varaha-datta, apparently two brothers who caused the statue to be made.

- Circular lead piece26 – script Mauryan Brahmi of 2nd century BCE – inscribed “Rano Indagutasa” translating King Indragupta

- Gajalakshmi clay seal27 – script Brahmi – reads “Airikine Gomika Visha(ya)” translating “the seal of the officer of Gomika vishaya of Airikina”

- A clay seal28 – Gupta Brahmi characters – read “Mahadandanayaka Simhanandi” translating “Simhanandi, a mahadandanayaka”

- Another clay seal29 – Brahmi characters – reads “Isvaramitraputrasya rajno Simhasrisenasya” translating “King Simhasrisena, son of king Isvaramitra”

Monuments – All the monuments of principal antiquities are located within one complex. There are remains of four-five temples, three main temples standing in a single line in the north-to-south direction. As per the epigraphs, the earliest construction happened during the Saka king and Mahakshtrapa Sridharavarman when a tirtha was established by building a ghat (flight of steps) at the river by Narayanasvami. A pillar was also erected by Satyanaga, the senapati (army general) and araksika (officer) of king, for the removal of calamities and the well-being of all creatures. The next phase of construction was during the reign of Samudragupta, however, whether it was a memorial pillar or a temple is a matter of conjecture as the portion mentioning the same in the inscription has only partially survived. While we have surviving pillars earlier and later than Samudragupta’s time, no pillar of Samudragupta has been found. Also, if there would have been a pillar then the inscription would have been on that pillar rather than on a separate stone slab. This suggests that Samudragupta’s inscription talks about a temple rather than a memorial pillar. Cecil and Bisschop point to some new epigraphs found at the site that suggest the possibility of a temple rather than a pillar.30

Nr-Varaha Statue – An exquisite sandstone statue representing Nr-Varaha was moved from here to Hari Singh Gaur University Museum, Sagar. This statue shows Varaha with a human body carrying Bhu-devi over his tusks. He is shown with two hands, standing in an alidha-posture keeping his one leg above a pillar. This statue would have been installed in a temple remains of which cannot be located. Including this temple, the complex would have three temples dedicated to different forms of Vishnu, Varaha, Narasimha, and Vishnu. The pedestal of the statue has a short inscription of two lines in Gupta Brāhmī script, which mentions the names Srī Maheśvaradatta and Varāhadatta, the two donors of the image, the relationship between those is not provided.

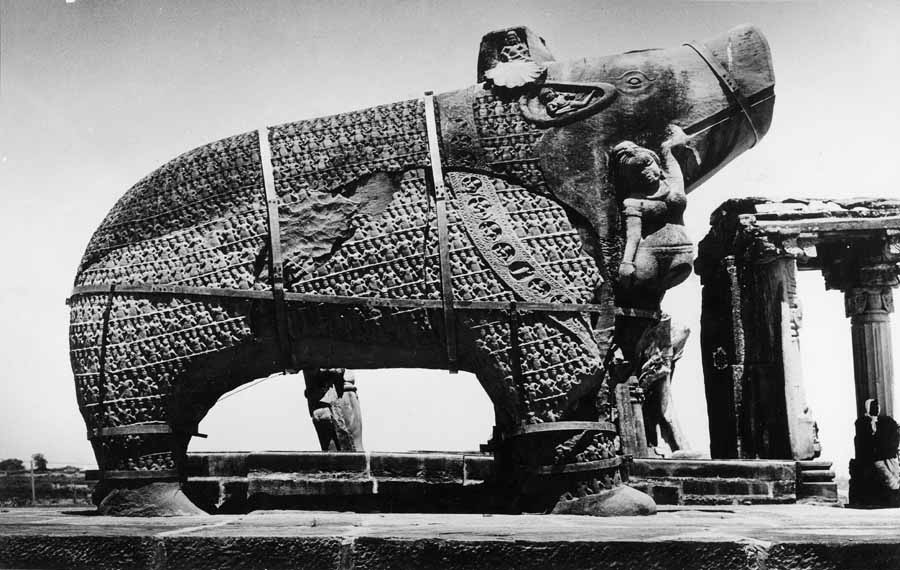

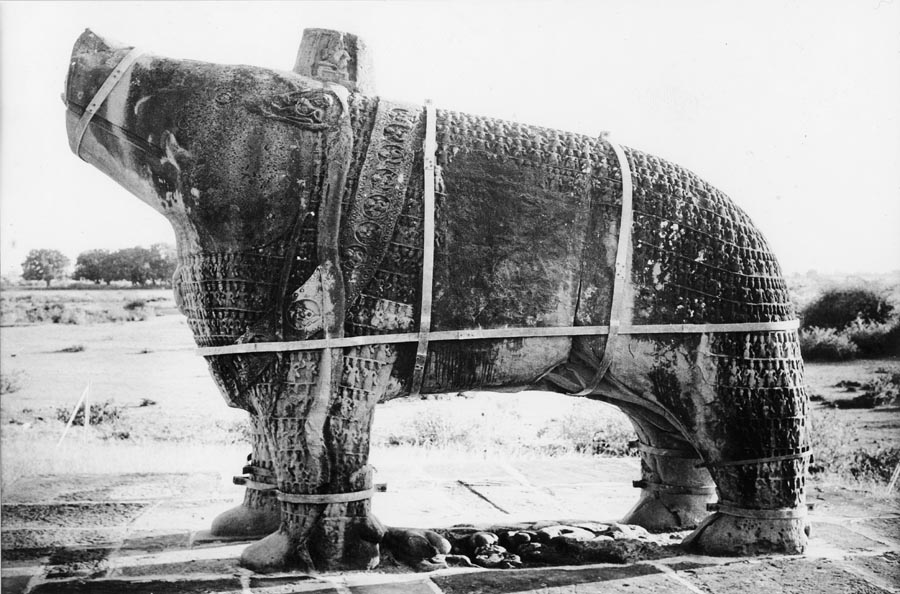

Varaha Temple – This image of Varaha stands over a pedestal in the open sky, however, once it may have been under a roofed enclosure. Cunningham mentions architectural fragments scattered around the statue as well as ruins of walls and pillars. The Varaha statue at Eran is the most ancient specimen of its kind. Varaha at Ramtek might be slightly earlier than that of Eran however, the one at Ramtek is a very simple representation of zoomorphic form and not the ornamented type as found in the later period. Varaha in its zoomorphic form is known as Yajna Varaha representing the yajna (sacrifice) with its aahutis (offerings) in an animated form. This Varaha image measures about 14 feet in length, 5 feet in width, and 12 feet in height31 making it the biggest such statue in India. The Varaha faces west and is ornamented with 1185 figures of sages, arranged in twelve rows, carved all over his body including legs, neck, forehead, and throat.32 This statue was commissioned by Dhanyavishnu, the younger brother of Matrvishnu, during the first regnal year of the Huna king Toramana in about 493-94 CE.

Let us have a look at various figures found on this Varaha. A figure of Bhudevi is shown hanging with the right tusk of Varaha. A female figure, her hands on her waist, is standing in sambhanga posture at the snout of the Varaha. Rangarajan33 identifies her with Sarasvati while Joanna Williams34 and Becker35 identify her with Vac, goddess of speech. Sarasvati might be a proper identification provided she is also found on the snouts of the Varahas at Khajuraho and Dudhai. A garland of twenty-eight circles (roundels) is carved around the neck of the Varaha. This garland has a male and a female figure alternating in each circle except one which has a figure of a scorpion. In an earlier article, Williams36 suggests that these roundels with male figures and a scorpion may represent the twelve zodiac (rashis) signs however later she changes her stand mentioning these roundels remain unexplained. Rangarajan37 suggests the twenty-seven roundels represent the twenty-seven nakshatra (constellations) of Hindu astrology and the scorpion figure indicates the statue of Varaha was installed during the Vrschik (Scorpio) rashi that is considered a very auspicious time for such activities.

Four rows of male figures are shown across the throat and chest area. There is a total of ninety-six figures, except the one, all are two-armed sages holding a water pot in one hand. Between the first and the second row, from the top, in middle is an image of Vishnu, who is shown standing on a lotus. He is shown with two hands, but both hands are broken. Rangarajan suggests that he might be holding a gada (club) and chakra (discus) and Becker agrees. The third row on the chest shows seven male figures, the leftmost holding two lotus in his hand and wearing a tunic while the rest holding a water vessel. This group of figures represents Saptagrhas (seven planets), the first figure from the left holding two lotus stems is Surya.38 Stephen Merkel mentions that these Saptagrahas are the earliest representation of the seven planets.39 Rahu and Ketu are excluded here as the early texts mention only the seven planets. The tunic Surya is shown wearing suggests the foreign influence as also attested by the fact that the statue was installed during the rule of Toramana.

On the shoulders of the Varaha is a stump-like protrusion that has four niches on its four sides. Rangarajan identifies the figures in the niches with Saumya Purusa (Vasudeva) on the west, Shiva on the south, Brahma on the north, and Vishnu on the east. She quotes Ahirbudhnya Samhita, where these four figures are identified with four vyuhas of the supreme being, namely, Vasudeva, Samkarshana, Pradhyumna, and Aniruddha. Joanna Williams40 suggests that this mound or stump on the Varaha’s back is a manifestation of Brahma and it might also represent a yupa or sacrificial post. Another proposition is that this stump represents a pillar as erecting commemorative pillars at Eran had been in practice as witnessed by the pillars of Budhagupta and Sridharavarman. It is very possible that Dhanyavishnu commissioned this image as a commemorative figure to honor the death of his brother, Matrvishnu, however, instead of following the pillar style he innovated and went for this Varaha image with a stump to suggest it is a commemorative pillar. However, we should be informed that the inscription over the image does not mention any such intention of the donor therefore whether it was for the purpose of commemoration is a matter of conjecture.

Twelve rows of figures, in the shape of a U, are carved along the body of the Varaha. All the twelve rows have figures of two-armed sages, holding water vessels in one hand and one hand either in abhaya-mudra or in vismaya-mudra. The legs and tail of the Varaha are also decorated with rows of sages, six rows in forelegs, and three rows in hind legs. Rangarajan41 is of opinion that these various sages, arranged in different rows in different parts of Varaha, represent the sages of Janaloka, who witnessed the episode of Varaha rescuing Bhudevi from the depths of an ocean. Becker42 points to the erection of this image during the rule of the Huna king Toramana. She digs deeper into the idea and the reason for erecting a Vaishnavite symbol or image in the reign of a foreign ruler. Installing a Vaishnavite image, which may be taken as an association with the previous Gupta rulers, might have brought wrath from the new Huna rulers. Though the Hunas are known as a barbaric and tyrant tribe, Becker tells that Toramana appears to be somewhat of a tolerant ruler. Becker quotes Thakur who mentions that Toramana, a shrewd statesman and foresighted administrator tolerated various religions of his subjects in order to maintain his authority as ruler. Becker tells that the Sassanians used boar as a symbol of royal authority however she also tells that the Sassanian boar imagery cannot be linked to Toramana directly or to the style of the Eran boar except the suggestion that boar was used as a royal symbol during the fifth and sixth century CE in the west and central Asia.

The two points which come to my mind are, how the donor of this statue got aware that boar could also be used as a royal symbol for the new ruler. And second is whether Toramana did not get the reading of the inscription which eulogized Narayana, a Hindu god. I believe that theory that Toramana allows some religious freedom to his subjects is more favorable here rather than Dhanyavishnu, the donor of the statue, getting the idea of using boar as Varaha as well as the royal symbol of Toramana.

Vishnu Pillar – This dhvaja-stambha was erected in the honor of god Janardana by two brothers, Matrvishnu and Dhanyavishnu during the reign of the Gupta king Budhagupta in about 484 CE. The pillar is erected over a rectangular platform of 13 feet square. The overall height of the pillar is about 47 feet. It is known locally as Bhim Gada. A major part of the pillar is underground. The shaft is square at the bottom till the height of 20 feet and then it turns octagonal for the next 8 feet till the capital. Two lions, seated back to back, are carved on the abacus of the capital.

The capital of the pillar is made of two human images, standing back to back with a wheel in between, one facing east and the other west. Cunningham tells that these figures were locally known as Rama and Lakshmana. However, both images represent Garuda. The one, facing east, shows Garuda holding a serpent in his hands which Bajpai43 takes as a representation of a crushing defeat of the Sakas under the Gupta emperor Chandragupta II. As Garuda is associated with serpents, as an enemy, it is not surprising to see him holding a serpent. Whether there was any political allegory behind this posture is a matter of conjecture. As per an inscription, this pillar was erected by brothers Matrivishnu and Dhanyavishnu during the rule of the Gupta king Buddhagupta. Matrivishnu was referred to as a king which suggests that he was ruling under the patronage of the Gupta emperors.

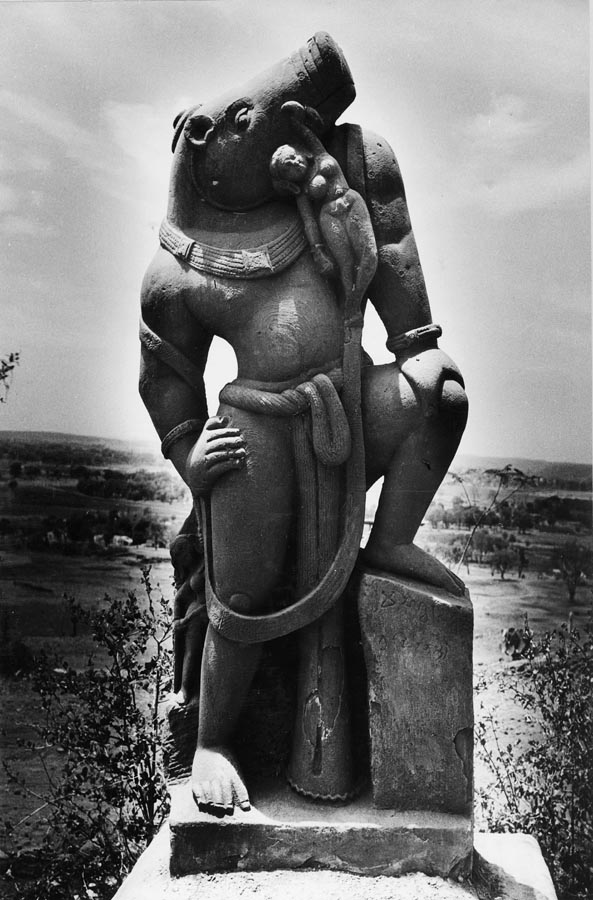

Narasimha Temple – This temple probably consisted of a sanctum and mandapa, the former was 12.5 feet long and about 9 feet wide as Cunningham mentions. Now only a damaged statue of Narasimha is what remains of this temple. It is broken below its knees however, its pedestal was in situ when Cunningham visited. Now the pedestal is also lying on the platform. The pedestal has the remains of the feet of Narasimha.

It would have been a 7 feet high statue in its original glory. The iconography is interesting as such this is a kevala-Narasimha image, shown standing but not in action. The mouth wide open shows an amiable appearance rather than the Rudra aspect as witnessed in other icons.

Vishnu Temple – This is the best-preserved temple at the site. Though its roof is fallen however its sanctum doorway is intact with its decoration. Cunningham suggests that, when complete, it would have measured 32.5 feet long and 13.5 feet wide while its interior dimensions would be 18 feet by 6 feet. Two pillars, 13 feet high, still standing in front of the sanctum suggests that a roofed mandapa adorned the temple. Only the pillars have survived, the walls between are all fallen.

An image of Vishnu, 13 feet high, is placed inside the sanctum. This image was known as an image of Bhim Sen by the locals as mentioned by Cunningham. The sanctum doorway has river goddesses, Ganga and Yamuna, at the door jambs. Usually, these river goddesses are found at the upper part of the door jambs during the Gupta period temples. Krishna Deva44 seems to agree here stating that the sanctum doorway and the front mandapa were installed during the Pratihara period of the 8th-9th century CE. Dvarpalas are present at the pilasters on either side of the door.

Various sculptures and architectural fragments have been assembled within the temple complex at Eran as well as many images from here have been carried off to the Museum of the Sagar University. Many of these fragments belong to the Pratihara period of the 8th-10th century CE suggesting the Eran temple complex was active during that period.

1 Chadhar, Mohan Lal (2017). Art Heritage of Eran, District Sagar (Madhya Pradesh) published in Indian Journal of Archaeology, October 2017. p. 398

2 Cunningham, Alexander (1878). Report of a Tour in Bundelkhand and Malwa and in the Central Provinces, vol. VII. Archaeological Survey of India. New Delhi. p. 90

3 Cunningham, Alexander (1880). Report of Tours in Bundelkhand and Malwa in 1874-75 and 1876-77, vol. X. Archaeological Survey of India. New Delhi. p. 77

4 Jayaswal, K P (1943). Hindu Polity. The Bangalore Printing & Publishing Co. Ltd. Bangalore. p. 160

5 Bajpai, K D (1976). Indian Numismatic Studies. Abhinav Publications. New Delhi. p 21

6 Bajpai, K D (1976). Indian Numismatic Studies. Abhinav Publications. New Delhi. p 22

7 Bajpai, K D (1976). Indian Numismatic Studies. Abhinav Publications. New Delhi. p 121

8 Bajpai, K D (1976). Indian Numismatic Studies. Abhinav Publications. New Delhi. p 19

9 Corpus Insciptionum Indicarum, Vol. IV, part II. pp. 605-611

10 Sircar, D C (1942). Select Inscription, Vol. I. University of Calcutta. Culcutta. pp. 180-181

11 Agrawal, Ashvini (1989). Rise and Fall of the Imperial Guptas. Motilal Banarsidass. New Delhi. ISBN 8120805925. p. 117

12 मिश्र, चंद्रलेखा (1976). एरण का राजनैतिक तथा सांस्कृतिक इतिहास, अप्रकाशित पी-एच. डी. उपाधि हेतु प्रस्तुत शोध-प्रबंध, सागर विशविद्यालय. अध्याय 5, पृ. 4

13 Bajpai, K D (1976). Indian Numismatic Studies. Abhinav Publications. New Delhi. p 101

14 Bajpai, K D (1976). Indian Numismatic Studies. Abhinav Publications. New Delhi. p 172

15 Bajpai, K D (1976). Indian Numismatic Studies. Abhinav Publications. New Delhi. p 131

16 मिश्र, चंद्रलेखा (1976) (अप्रकाशित). एरण का राजनैतिक तथा सांस्कृतिक इतिहास, पी-एच. डी. उपाधि हेतु प्रस्तुत शोध-प्रबंध, सागर विशविद्यालय. अध्याय 5, पृ. 5

17 Agrawal, Ashvini (1989). Rise and Fall of the Imperial Guptas. Motilal Banarsidass. New Delhi. ISBN 8120805925. p 242

18 Agrawal, Ashvini (1989). Rise and Fall of the Imperial Guptas. Motilal Banarsidass. New Delhi. ISBN 8120805925. p 235

19 चढ़ार, मोहन लाल (2007) (अप्रकाशित). एरण की ताम्रपाषण संस्कृति : एक अध्ययन, डॉ. हरीसिंह गौर विश्वविद्यालय, सागर की पीएच। डी. उपाधि हेतु प्रस्तुत शोध-प्रबंध। पृ.23-24

20 No. 2 of Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum, Vol. III. pp. 18-20

21 No. 19 of Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum, Vol. III. pp. 88-91

22 No. 36 of Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum, Vol. III. pp. 158-161

23 No. 20 of Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum, Vol. III. pp. 91-93

24 Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum, Vol. IV, part II. pp. 605-611

25 Descriptive List of Inscriptions in The Central Provinces and Berar

26 Bajpai, K D (1976). Indian Numismatic Studies. Abhinav Publications. New Delhi. p. 23

27 Bajpai, K D (1976). Indian Numismatic Studies. Abhinav Publications. New Delhi. p. 172

28 Bajpai, K D (1976). Indian Numismatic Studies. Abhinav Publications. New Delhi. p. 172

29 Bajpai, K D (1976). Indian Numismatic Studies. Abhinav Publications. New Delhi. p. 172

30 Cecil & Bisschop (2021). Idiom and Innovation in the ‘Gupta Period’: Revisiting Eran and Sondhni published in The Indian Economic and Social History Review, Vol. 58, Part 1. p. 42

31 Cunningham, Alexander (1878). Report of a Tour in Bundelkhand and Malwa and in the Central Provinces, vol. VII. Archaeological Survey of India. New Delhi. p. 83

32 Rangarajan, Haripriya (1997). Varaha Images in Madhya Pradesh. Somaiya Publications. New Delhi. ISBN 8170392144. pp. 48-55

33 Rangarajan, Haripriya (1997). Varaha Images in Madhya Pradesh. Somaiya Publications. New Delhi. ISBN 8170392144. pp. 48-55

34 Williams, Joanna Gottfried (1982). The Art of Gupta India – Empire and Province. Princeton University Press. New Jersey. ISBN 0691039887. p. 130

35 Becker, Catherine. Not Your Average Boar: The Colossal Varaha at Eran, An Iconographic Innovation published in Artibus Asiae, vol. 70, no. 1. pp. 123-149

36 Williams, Joanna Gottfried (1982). The Art of Gupta India – Empire and Province. Princeton University Press. New Jersey. ISBN 0691039887. p. 130

37 Rangarajan, Haripriya (1997). Varaha Images in Madhya Pradesh. Somaiya Publications. New Delhi. ISBN 8170392144. pp. 48-55

38 Williams, Joanna Gottfried (1982). The Art of Gupta India – Empire and Province. Princeton University Press. New Jersey. ISBN 0691039887. p. 130

39 Markel, Stephen

40 Williams, Joanna Gottfried (1982). The Art of Gupta India – Empire and Province. Princeton University Press. New Jersey. ISBN 0691039887. p. 130

41 Rangarajan, Haripriya (1997). Varaha Images in Madhya Pradesh. Somaiya Publications. New Delhi. ISBN 8170392144. pp. 48-55

42 Becker, Catherine. Not Your Average Boar: The Colossal Varaha at Eran, An Iconographic Innovation published in Artibus Asiae, vol. 70, no. 1. pp. 123-149

43 Bajpai, K D (1976). Indian Numismatic Studies. Abhinav Publications. New Delhi. p. 20

44 Deva, Krishna (2000). Temples of India. Aryan Books International. New Delhi. ISBN 8173050546. p. 13

Web References

- http://travellingslacker.com/2016/09/eran-a-porcine-nostalgia/#.V_pyWSQ3lNz, retrieved on 09 October 2016

- https://visvarupa.com/2015/12/11/n%E1%B9%9Bvaraha-delivering-the-goddess-earth/, retrieved on 06/11/2021

Eran is really an important place. It was a city state with their coinage.

@ Mr PNS, Yes I agree with you however this place is so remote and not easily approachable. It was pretty hard to find this place, if being and Indian and Hindi spoking person felt so hard, I think how foreign origin people will go there.

Dear Saurabh, Thanks for the murtis from Eran. I wanted to go there when I was on a tour, but they wouldn't agree. It is SOOO old!

Beautiful doorway. Glad you took the trouble to find it.

Actually I was on a tour w Dr. Michell when he said 'no'. No wonder, too difficult to take a group there.

I also came across a 4′ high Varaha similar to that of Eran at a village known as Bhelsi in Tikamgarh district.

I wish I could take a closer look at the statues on the tower.Someone with a greater optical zoom camera would have to go there and take pictures.I think by erecting stone pillars

with lions and Chakra capital, Guptas are trying to put themselves with the ancient imperial power like Mauryas.May be the iron pillar at Delhi once had a capital like this.

Hi Dhananjay,

I did not have a good zoom camera at that time so could not take a better pic, if I visit again I will surely take a good pic of this capital. As the Guptas were the Vaishnavas in character and used Garuda as their banner so presence of Garuda on their capitals is not at all surprising. The capital of the iron pillar has not survived however as it is referred as the Vishnu-dhwaja so we can say that there would have been a capital of Vaishnava character.

Thanks a lot for the info… there is hardly any other good source online… will be doing it soon…

Comments are closed.