The sky with its luminaries and respective movement would have bewildered mankind since the very start. Like the other natural phenomena, i.e. floods, lighting, rains, etc. the luminaries in the sky were also considered as super-natural powers worthy of worship or special treatment. Our ancestors would have observed that many luminaries were stationary and many had movements. The stationary nature of the Pole Star made our ancestors believe that all the celestial bodies were attached to the Pole Star and revolved around it in a specific path. The movements of the celestial bodies would have been used in the calculation of time, days, and seasons. As time progressed, these celestial bodies were deified with a proper iconography assigned to them. Visibility of certain bodies at a certain specific time or period would have also called for identifying good and bad omens. The science of astrology and astronomy thus developed in India since the earliest civilization of the land.

The term nava-grahas refers to the group of nine grahas (planets), Surya (Sun), Chandra (Moon), Budha (Mercury), Mangala (Mars), Shukra (Venus), Brhaspati (Jupiter), Shani (Saturn), Rahu, and Ketu. These grahas traverse across the sky passing through different nakshatras (constellations), thus casting influence over the happenings and future events for a person or a country. Worship and appeasement of these grahas through different means and devices are very popular in Indian culture and astrology. In many temples across India, you can witness a nava-graha slab or group of graha images set in the temple compound for worship. Nava-graha temple circuit of Tamilnadu is famous for pilgrimage and religious aspects.

However, the number of grahas was not always fixed to nine, as we find references in the ancient Indian literature suggesting fewer than nine grahas, sometimes seven and sometimes eight. Our ancestors of the Vedic period would have observed the sky and understood the moving and the stationary celestial bodies. They would have observed the stars and constellations as stationary while Surya, Chandra, and planetary bodies as moving celestial bodies. They would have also seen solar and lunar eclipses and may have assumed a shadow object enveloping over the Surya and Chandra causing that phenomenon. They probably took this shadow object as a graha of dark color which is only visible when it comes in front of a luminary body, and at other times remains hidden or invisible to a human eye. This dark or invisible graha is held responsible for eclipses and personified as a demon as we find him in Rigveda. Rigveda is the oldest of the Vedas and may be dated somewhere between 1500-1000 BCE. While there is no definitive reference of grahas in Rigveda, it mentions an asura Svarbhanu who pierces Surya with darkness.1 This made Surya fall down and lose his position. Later Atri found the Surya and restored it to its previous position. Svarbhanu thus represents the personification of the graha responsible for the solar eclipse. Hale2 mentions the verses about Svarbhanu in Rigveda may be of the late origin or part of a different hymn as these verses differ in their meter from the previous verses of that hymn. In Atharva Veda, dated 1200-1000 BCE, Rahu is mentioned as the grasper of Chandra. Thus, Rahu represents the personification of the lunar eclipses. Atharva Veda also mentions grahas, without giving names, as wanderers in heaven.3

Chandogya Upanishad, dated between 800-600 BCE, mentions Chandra freeing itself from the mouth of Rahu.4 From all the above references, we may conclude that the concept of planets was not fully developed during the Vedic period. While the Vedic people might be aware of the different planetary bodies being visible at different periods and times of the day, however, they did not classify those bodies into groups or individuals. One classification the Vedic people were able to make was with the Solar and Lunar eclipses as these events would be visible and evident to them, Svarbhanu was responsible for the Solar eclipse while Rahu was responsible for the Lunar eclipse.

One of the earliest available astrological treatises is probably the Parasara-tantra5, which has not survived in full but only in its reconstruction utilizing references from various later commentaries. The text mentions five planets Mangal, Budha, Brhaspati, Shukra, and Shani, who with Surya and Chandra (Soma) constitute a group of seven celestial bodies. Parasara-tantra includes Rahu as a graha, however, mentions it as an invisible body responsible for eclipses, both Solar and Lunar. Ketus are mentioned in the plural and in the context of comets but not as a planet. Parasara-tantra enumerates 101 Ketus.

Yavanajataka of Sphujidhvaja, dated between the 4th-6th century CE, is a Sanskrit translation of a Greek text. It is an important astrological work as it reflects the intermingling of Indian and Hellenistic (Greek) ideas and the exchange of information. In the Yavanajataka, the seven planetary deities are mentioned as Surya, Chandra, Shukra, Brhaspati Budha, Angaraka, and Shanaichchara.6 The seven planets of Yavanajataka appear to be influenced by the seven planets of Hellenistic astrology, Sun, Moon, Venus, Jupiter, Mercury, Mars, and Saturn as both follow the same sequence and order.

Brihat-Samhita of Varahamihira, dated 6th century CE, is a very important work in the ancient Indian astrological field and is considered a landmark as the author collected all the available information from the past authors and provided a compendium. Varahamihira questions the validity of Rahu as a planet.7 He quotes a tradition of Rahu turning into a planet though his head was cut-off as him tasting nectar. His head resembles the orbs of other planets however he is not visible in the sky being of dark color except during eclipses. He mentions that authors before him have declared Rahu having a serpentine form with head and tail only and few said he is formless and of pure darkness. Varahamihira questions if Rahu has a circular body with head and tail and has affixed and uniform motion then how he can seize the Sun and Moon, as these both are located at 180° to each other during eclipse time. Or if Rahu does not have a fixed motion, then how its position be determined by calculation? Or if this Rahu has a big body such that by its mouth it seizes the Moon and by its tail, the Sun, why it does not obstruct half of the zodiac falling between is his head and tail? Or if there be two Rahu, then when one is seizing the Sun and the other should seize the Moon, but that is not practical. Similar to Parasara, Varahamihira also explains Ketus as comets but not as a planet. In his Brihajjatakam, Varahamihira includes Ketu under planets however did not provide as many details as he did for other planets. His use of the synonym Shikhin for Ketu suggests that Ketu was still treated as comets.

In the Puranic period, Rahu and Ketu started being included in the graha-group. The dating of Puranas is a complicated matter as these were constantly modified and extended throughout history. While describing the Upper Regions, Brahma Purana mentions the position and distance of celestial bodies from the Earth. Among these bodies, the Purana includes Surya, Chandra, Budha, Usanas (Shukra), Angaraka (Mangal), Brhaspati, and Shani.8 Beyond Shani is told the sphere of the Sapta-rishis (the Great Boar). Dhruva star (Pole star) is said to be the pivot of entire luminaries and is said to be situated above the Sapta-rishis. As our ancestors would have witnessed the Pole Star is always in the same location, therefore this might have led them to assume Pole Star as the pivotal point in the universe. Brahma Purana reiterates the Rigvedic tradition of Rahu seizing Surya, telling that sage Prabhakara, of the family of Atri, reinstated Surya and saved him from falling down after the latter was eclipsed by Rahu.9 When Daksha paid obeisance to Shiva, he uses Svarbhanu as another name for Rahu.10 In the episode of Amrtasangama, the Purana mentions the story of Rahu drinking the divine nectar. Rahu, the son of Simhika, in disguise as a devata drank the nectar. When Chandra (Soma) informed Vishnu, the latter cut the body of Rahu into two, the head and the rest. The head immediately became immortal and his immortal headless body fell on the earth. The devatas were feared if the head could be united with its body then it would cause an end to the world, therefore they prayed to Shiva who sent his Shakti to devour the body. Rahu, in form of his immortal head, gave the secret of destructing his body and with this act, he became the same as the devatas. Shakti and the mothers extracted the vital juices from the body and nectar. These juices flew out of his body and created river Pravara.11 In another episode of the penance of Meghahasa, the son of Rahu, the Purana tells that the Devatas made Rahu the follower of planets and graced with all the honors.12

In the chapter on planet worship, Padma Purana includes all the nine planets and provides details of how to worship and please those.13 In the chapter on the birth of Lakshmi, the Purana mentions that Vishnu struck Rahu with the golden pot after the latter drank the divine nectar. The body of Rahu was split into two, Rahu and Ketu.14 Vishnu Purana follows Brahma Purana while describing the seven spheres, Surya, Chandra, Budha, Shukra, Angaraka, Brhaspati, and Shani15 however it includes Rahu and Ketu while describing the chariots of the planets.16 Shiva Purana17 follows other Puranas while describing the seven spheres above Earth which does not include Rahu and Ketu however, it enumerates a total number of planets as nine at various places. Additionally, the Purana narrates an account of Chandra being borne on Shiva’s hair and Shiva fixing the head on the neck of Rahu and thus creating Ketu18. While describing the rules of nyasa in the path of renunciation, the Purana mentions the worship of planets but excludes Ketu in the group.19 However, while describing kamya rites, the Purana includes Ketu among other planets for worship.20 Matsya Purana describes the iconography of nava-graha including that of Rahu and Ketu.21

In the episode of the samudra-manthana in the Skanda-Purana22, on the emergence of Chandra out of the ocean, sage Garga explains that all the planets were powerful that day. Among the planets apart from Chandra, Garga mentions Guru (Brhaspati), Budha (Mercury), Shukra (Venus), Shani (Saturn), Angaraka (Mars), and Surya (Sun) but not Rahu and Ketu. Later we find Rahu and Ketu being mentioned among the list of the Danavas sat in order to receive nectar from Mohini.23 As Rahu and Ketu sat in the rows of the Devatas and drank nectar, this was reported to Vishnu by Surya and Chandra. Vishnu cut the head of Rahu while Ketu vanished into the sky in the form of smoke.24 The Purana does not mention anything further on what happened to Rahu and Ketu. In the chapter on the position of the higher world, Skanda-Purana explains the position of eight celestial bodies, Surya, Chandra, Budha, Usanas (Shukra), Bhauma (Mangala), Bhrhapati, Shani, and Svarbhanu (Rahu).25 In the chapter on the creation of the Moon, the Purana mentions the Rigveda tradition of Svarbhanu seizing Surya, stating when Surya was struck by Svarbhanu and the lord fell to the ground from heaven, the whole world was assailed with darkness. It was the Brahmanical sage Atri who restored Surya and caused light to function. Thus, Atri is also known as Prabhakara as he restored the Surya to its position.26

Brahmanda Purana enumerates different numbers of planets at different places. While explaining the origins of luminaries, the Purana tells that everything has emerged out of Surya and therefore Surya is the lord of the planets, and Chandra is the lord of the stars.27 Here the Purana enumerates five planets Angaraka (Mars), Budha (Mercury), Sanaichara (Saturn), Shukra (Venus), and Brhaspati (Jupiter). While describing the chariots of the planets, the Purana enumerates nine planets in total with the inclusion of Rahu and Ketu.28 While describing the permanent abodes of the planets, where these bodies retire to at the end of the manvantara, the Purana only describes abodes of the eight planets excluding Ketu. It refers to Rahu as Svarbhanu and tells that abode of Svarbhanu is dark and causes distress to all living beings. It tells that Svarbhanu is called so as it pushes away the heaven (svar) by means of its splendor (bhasa). While describing the birth stars of these planets, the Purana mentions Sikhin (Ketu) being born in the constellation of Aslesha and Rahu in the constellation of Bharani.29

Linga Purana follows other Puranas while describing the spheres of planets and their movements with their chariots. In few places, it excludes Ketu while describing other planets.30 Rahu is mentioned as Svarbhanu and Ketu as Shikhin. Ketu is mentioned as a son of Mrtyu and born of the constellation Ashlesha while Rahu, son of Simhika, and born of the constellation Bharani. While describing the planets and their relative positions, Garuda Purana enumerates chariots and movements of all the nine planets, including Rahu and Ketu.31 Padma Purana includes worship of Rahu and Ketu in its chapter on the worship of planets.32 Narada Purana is an important text as it includes considerable astrological information. It includes Rahu and Ketu as planets when it comes to pacification and appeasement of those as deities33. However, while describing the delineation of horoscopy, it mentions seven but not nine planets stating that as an opinion of the leading luminaries in astrology34 and includes Rahu with the seven planets as the lord of the eight quarters35. In chapter fifty-six on natural astrology36, the Purana tells Rahu is responsible for solar and lunar eclipses. Rahu is said to be the head of the demon that attained immortality due to tasting ambrosia. In the same chapter, it mentions Ketu as comets. In the chapters of asterism, the Purana discusses conjunctions of other planets with Rahu however it does not mention conjunctions with Ketu.

Kurma Purana mentions Surya presides over the other eight planets and refers Rahu as Svarbhanu and Ketu as Bhaskarari.37 Brahmavaivarta Purana mentions different legends about Rahu eclipsing Surya and Chandra. It tells sage Jamadagni cursed Surya to be eclipsed by Rahu as the latter tried to preach the sage about dharma etc. Similarly, Tara cursed Chandra to be eclipsed by Rahu when the latter abducted her for pleasure.38 It is told that due to these curses, it is advised not to look at Surya and Chandra when either is in eclipse. In chapter fifty-two about the Pole Star and its movement, Vayu Purana mentions the chariots of Rahu and Ketu.39 In chapter fifty-three on the arrangement of luminaries, Vayu Purana does not include Ketu but mentions Svarbhanu (Rahu), son of Simhika.40 In the same chapter, the Purana tells like Surya is the first among the planets and Shukra is the first among the stellar planets, similarly, Ketu is first among the comets.

Among all the grahas, Surya is the supreme and a lot of legends have been associated with him. He has been depicted abundantly in varied iconography in Indian sculpture. The second important body is Chandra (Moon), the son of sage Atri with Aunusya. While Surya is found in an individual capacity in temples, Chandra seldom appears solo. In many cases, he is portrayed with Surya to suggest perpetuity. The other planets are mostly carved in groups, very seldom in an individual capacity. They are mostly worshiped for their astrological properties impacting mankind. Budha (Mercury) is the illegitimate son of Chandra with Tara, the wife of Brahaspati. Mangala (Mars) is the son of Shiva with Bhu-devi (Earth). Shukra (Venus) is the guru of asuras and Brahaspati is the guru of devas. Rahu is the son of Simhika and grasper of Surya and Chandra. The last planet, Ketu, is generally referred to in the context of comets. It would be probable that Ketu (or comets) of astronomy became Ketu as a graha in astrology. As a graha, Ketu started being included in the graha group during or after the 7th century CE in the Hindu and Buddhist sculptures. However, the Jains were very reluctant to accept the ninth graha Ketu as we find images with eight grahas as last as the beginning of the second Millenium.41 In Indian sculpture, there are instances of sapta-grahas (seven planets) and ashta-grahas (eight planets), most of these pre-dating the nava-graha iconology. The earliest sculptural representation of grahas in Indian art is over the yajna-Varaha figure at Eran (Madhya Pradesh), dated the 5th century CE.42 On the chest of the Varaha are carved seven standing figures representing seven planets. Surya, first in the group, is wearing a tunic dress and holding a lotus in both hands. This depiction of seven planets connects to the Hellenistic tradition of seven planets corresponding to the seven days of a week.

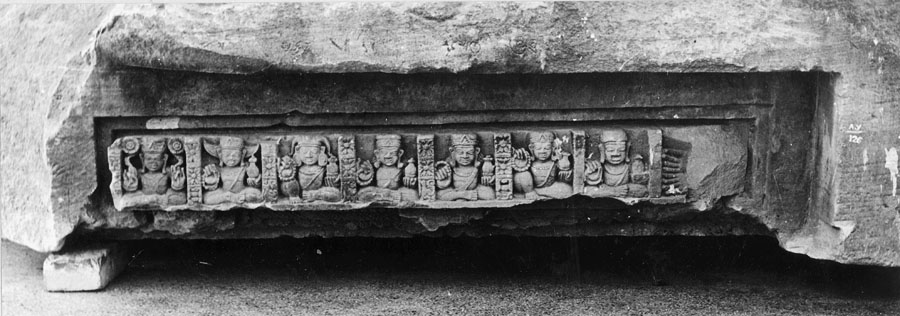

While we do not find grahas on the surviving Gupta temples, there are few Gupta period sculptures, one in the Indian Museum, Kolkata, and another in the Worcester Art Museum, depicting eight grahas excluding Ketu. Many ashta-graha sculptures are reported from Odisha and Bihar. In Bhubaneswar, the Shatrughnesvara group and the Parasurameshvara temple, belonging to the Shailodbhava period of the 6th-7th century CE, have the doorway lintel block decorated with ashta-grahas comprising Aditya (Surya), Soma (Chandra), Angaraka (Mangal), Budha, Brhaspati, Shukra, Shanicchhar (Shani) and Rahu. Ketu is excluded from this group. Similarly, ashta-graha sculptures from Bihar depict all the planets except Ketu. These early graha panels of Odisha are inscribed, indicating it was early experimentation and the labels were to help the common public to understand the names of the grahas.

1 Rigveda Book 5, hymn 40

2 Hale, Wash Edward (1986). Asura – in Early Vedic Religion. Motilal Banarsidass. New Delhi. ISBN 8120800613. pp 64-65

3 Atharva Veda Book 19, hymn 9

4 Chandogya Upanishad Chapter 8, Khanda 13, Sholka 1

5 Iyengar, R N (2008). Archaic Astronomy of Parasara and Vrddha Garga published in Indian Journal of History of Science.

6 Yavana-jataka

7 Brhat-samhita

8 The Brahma Purana, Part I. Motilal Banarsidass. New Delhi. ISBN 8120800036. p 121

9 The Brahma Purana, Part I. Motilal Banarsidass. New Delhi. ISBN 8120800036. p 70

10 The Brahma Purana, Part I. Motilal Banarsidass. New Delhi. ISBN 8120800036. p 223

11 The Brahma Purana, Part IV. Motilal Banarsidass. New Delhi. ISBN 8120800036. pp 882-85

12 The Brahma Purana, Part IV. Motilal Banarsidass. New Delhi. ISBN 8120800036. pp 1074-75

13 Deshpande, N A (1989). Padma Purana part II. Motilal Banarsidass. New Delhi. ISBN 8120805836. pp 891-895

14 Padma Purana part V. Motilal Banarsidass. New Delhi. p 1591

15 Vishnu Purana. The Christian Literature Society. Madras (now Chennai). p 17

16 Wilson, H H (1840). Vishnu Purana. John Murray. London. p 240

17 Shiva Purana Part III. pp 1529-30 | Shiva Purana part I. p 28

18 Shiva Purana part III. p 1140

19 Shiva Purana part IV. p 1693

20 Shiva Purana part IV. p 2029

21 Basu, B D (ed.) (1916). The Sacred Books of the Hindus vol. 17, part I – Matsya Puranam. AMS Press. New York. ISBN 0404578179. pp 257-258

22 Tagare, G V (1992). Skanda Purana Part I. Motilal Banarsidass. New Delhi. ISBN 8120809661. pp 85-86

23 Tagare, G V (1992). Skanda Purana Part I. Motilal Banarsidass. New Delhi. ISBN 8120809661. p 93

24 Tagare, G V (1992). Skanda Purana Part I. Motilal Banarsidass. New Delhi. ISBN 8120809661. pp 95-96

25 Tagare, G V (1993). Skanda Purana Part II. Motilal Banarsidass. New Delhi. ISBN 9788120810228. pp 309-312

26 Tagare, G V (1960). Skanda Purana Part XIX. Motilal Banarsidass. New Delhi. p 121

27 Tagare, G V (1983). Brahmanda Purana part I. Motilal Banarsidass. New Delhi. ISBN 812080354X. p 236

28 Tagare, G V (1983). Brahmanda Purana part I. Motilal Banarsidass. New Delhi. ISBN 812080354X. p 230

29 Tagare, G V (1983). Brahmanda Purana part I. Motilal Banarsidass. New Delhi. ISBN 812080354X. p 245

30 Sharma, Shriram Acharya (1969). Linga Purana part I. Sanskrti Sansthan. Bareilly. pp 223-238 | 341-342

31 Shastri, J L (ed.) (1978). Garuda Purana part I. Motilal Banarsidass. New Delhi. ISBN 9788120803442. pp 191-194

32 Deshpande, N A (1989). Padma Purana Part II. Motilala Banarsidass. New Delhi. ISBN 8120805836. p 891-893

33 Narada Purana part II. Motilal Banarsidass. New Delhi. p 645

34 Narada Purana part II. Motilal Banarsidass. New Delhi. p 725

35 ibid.

36 Narada Purana part II. Motilal Banarsidass. New Delhi. pp 778-88

37 Kurma Purana. Motilal Banarsidass. New Delhi. p 292

38Nagar, Shanti Lal (2003). Brahmavaivarta Purana vol. I. Parimal Publications. New Delhi. ISBN 8171101704. pp 511-518

39 Vayu Purana part I. p

40 Vayu Purana part I. p

41 Mevissen, Gerd J R (2012). Figuration of Time and Protection: Sun, Moon, Planets and other Astral Phenomena in South Asian Art published in Figuration of Time in Asia. Wilhelm Fink Verlag. Munich. ISBN 9783770554478. p 115

42 Markel, Stephen (1991). The Genesis of the Indian Planetary Deities published in East and West, Vol. 41, No. 1/4. p 184